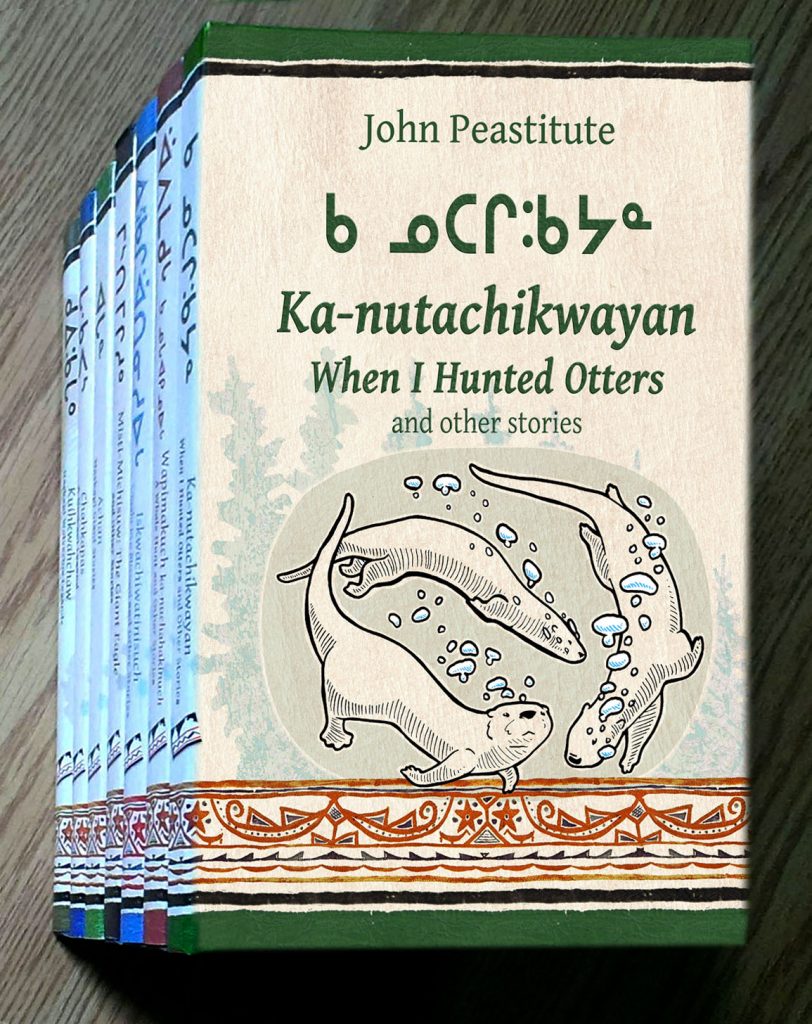

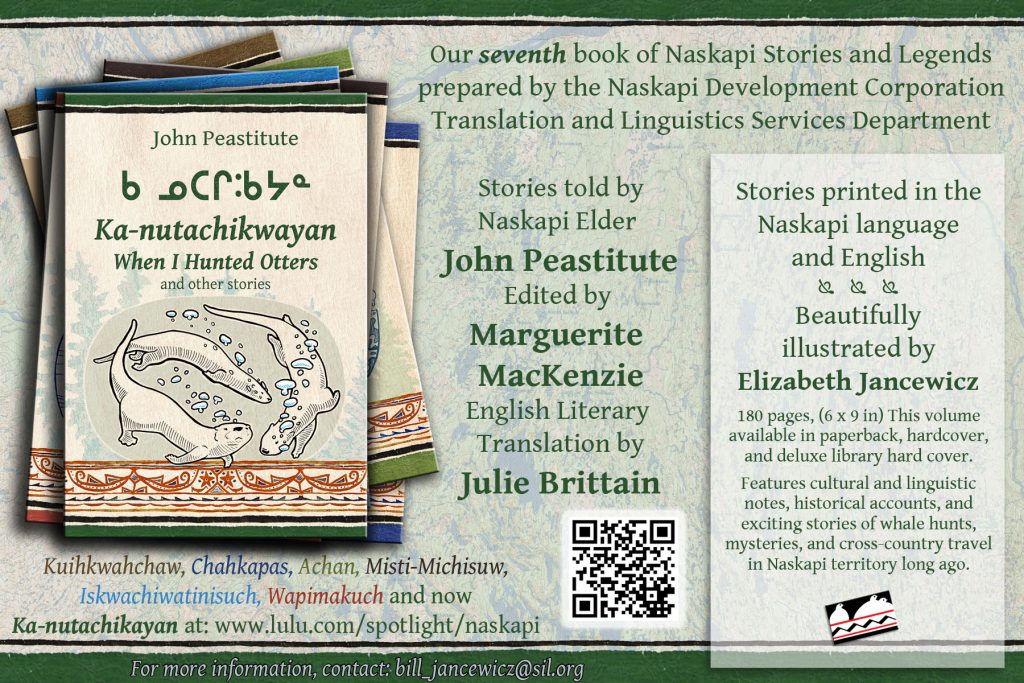

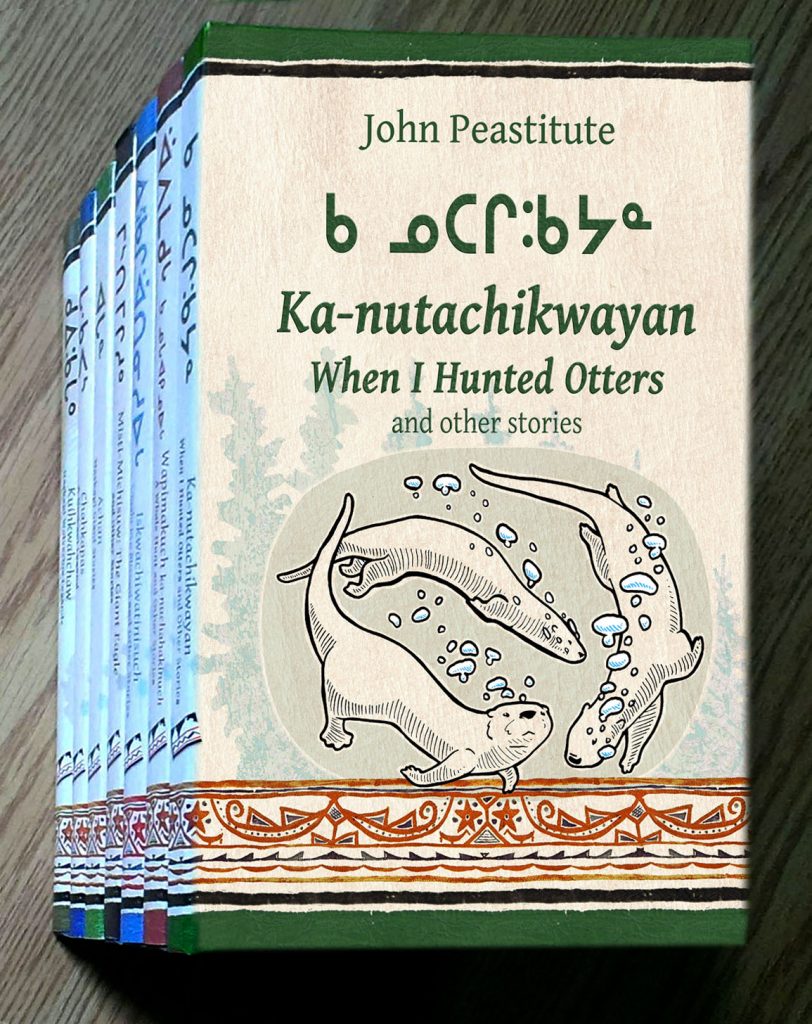

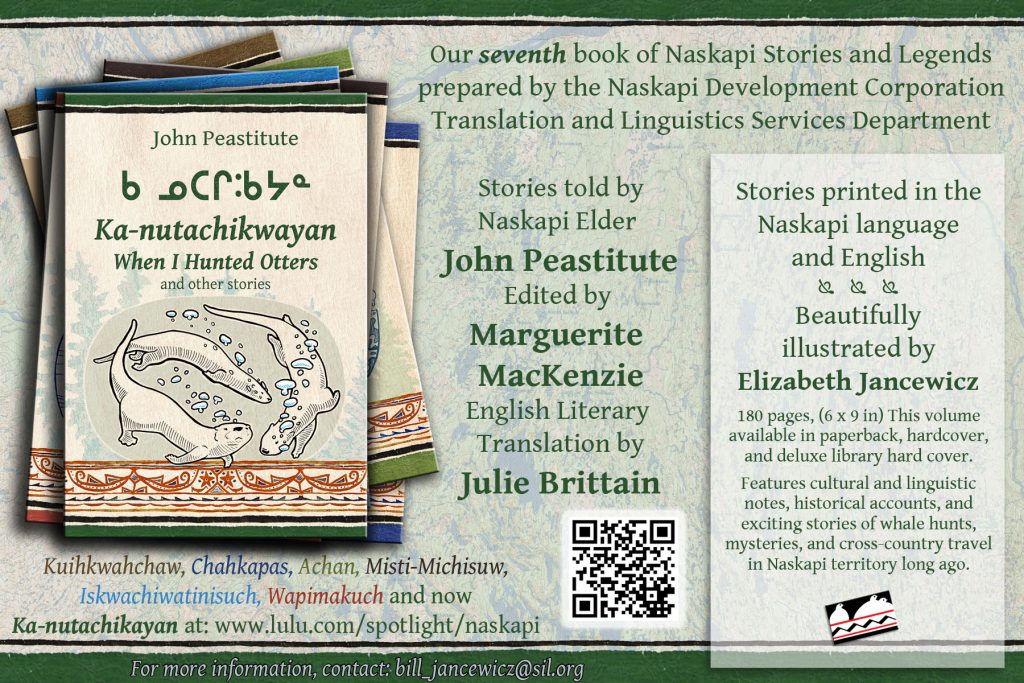

The newest book in the Naskapi Legends and Stories project, Ka-nutachikwayan: When I Hunted Otters and other stories, has just been completed! (Summer, 2021)

This book contains five more original Naskapi stories for reading in the Naskapi language, with a literary English translation, historical and linguistic notes, and beautifully illustrated by Elizabeth Jancewicz.

This book contains five more original Naskapi stories for reading in the Naskapi language, with a literary English translation, historical and linguistic notes, and beautifully illustrated by Elizabeth Jancewicz.

Kinuwâpinuw: One family’s story of an encounter with spirits, and what came of it, with actual locations provided on maps.

Kâpisâukin: Murder and revenge in the early days of the fur trading posts.

Kâ-nûtâchikwâyân: Another engaging memoire of John Peastitute of winter hunting on the land, this time having to do with otters.

Wâpinûtâhch kâ-ispiyinânûuch: The tale of a long journey from inland to the east coast of Labrador, and back. This fascinating story begins in summer 1935 (by canoe) and ends in mid winter (by snowshoe) and has detailed accompanying maps, identifying placenames and people.

Miskâhtuyâpâw: An amazing account of an amazing Naskapi man that has been passed down to the storyteller from generations before him, recounting events that apparently took place during the second half of the 1800s. Maps and placenames accompany this story too.

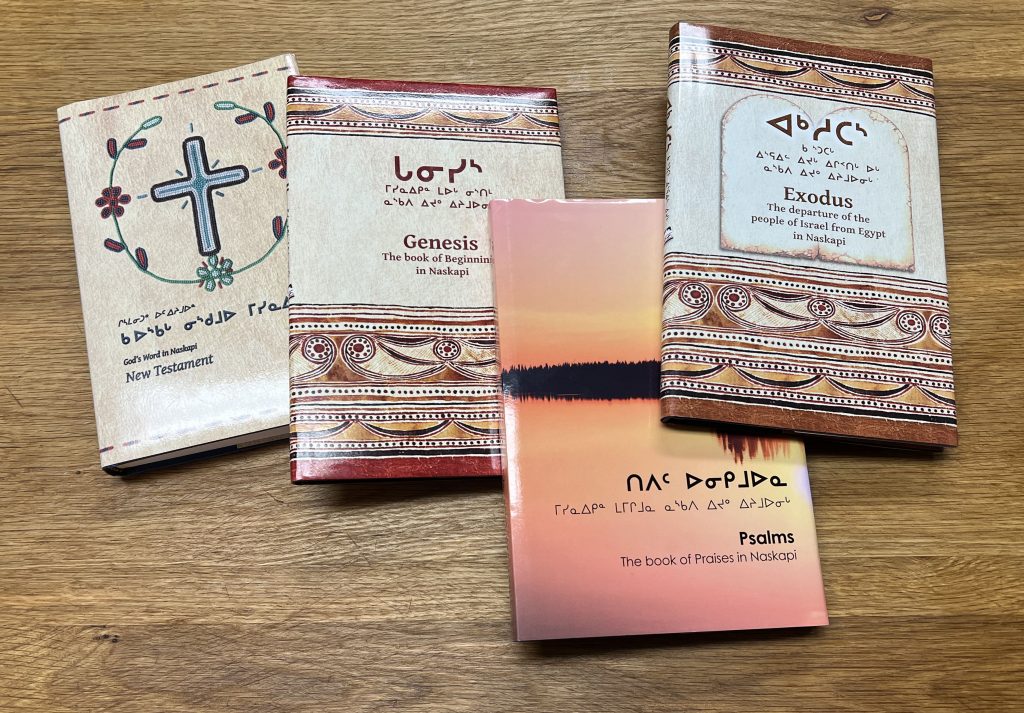

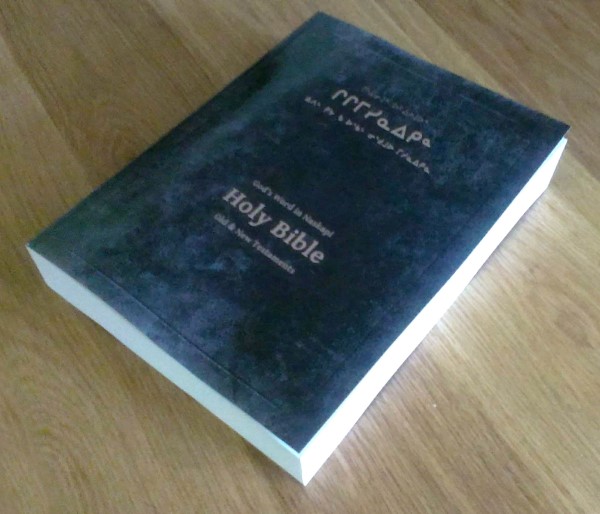

Naskapi Language Literacy

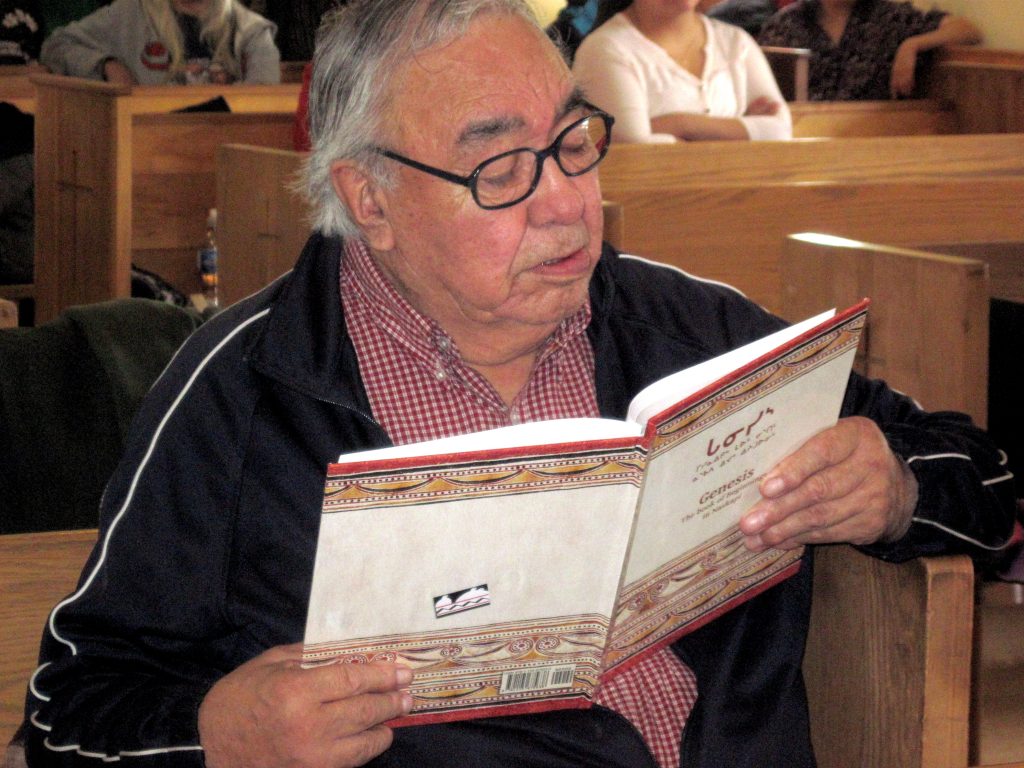

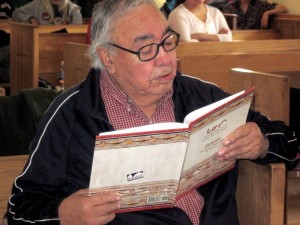

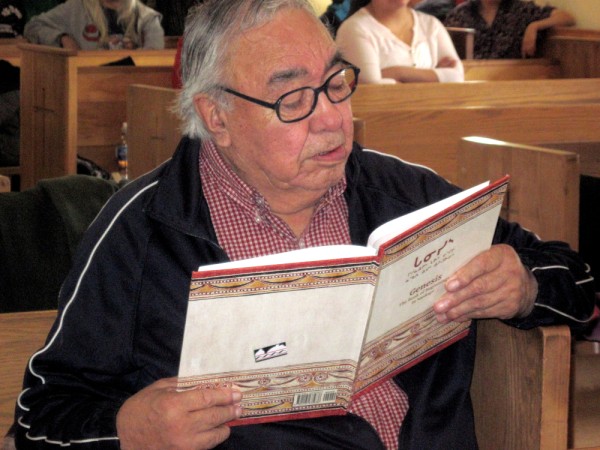

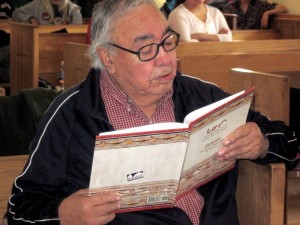

The late elder Joseph Guanish reading the new edition of Naskapi Genesis in 2013

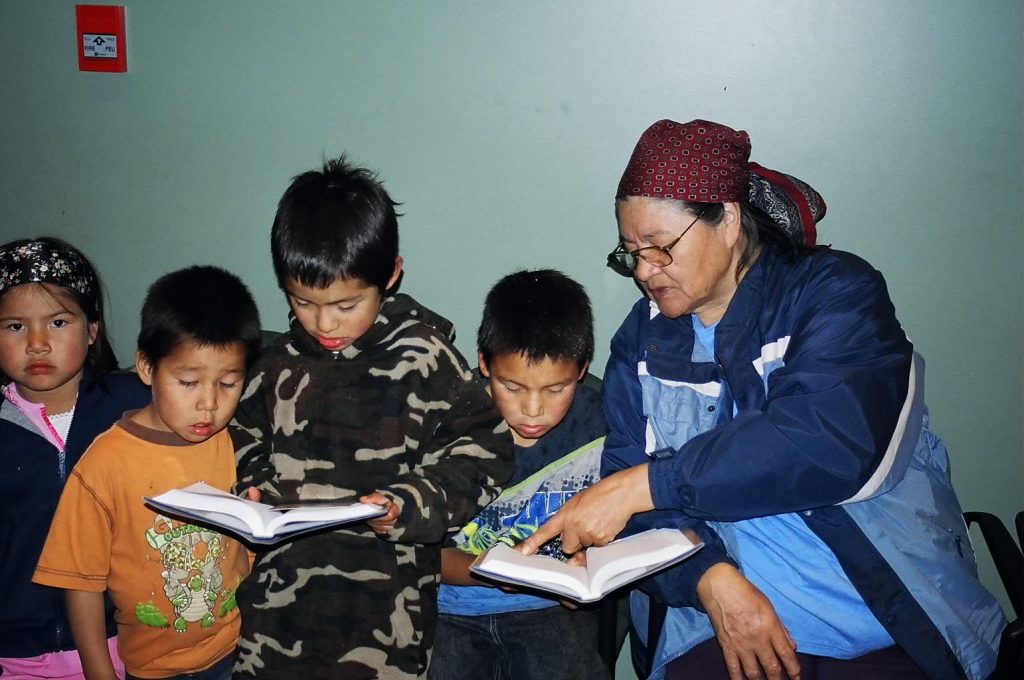

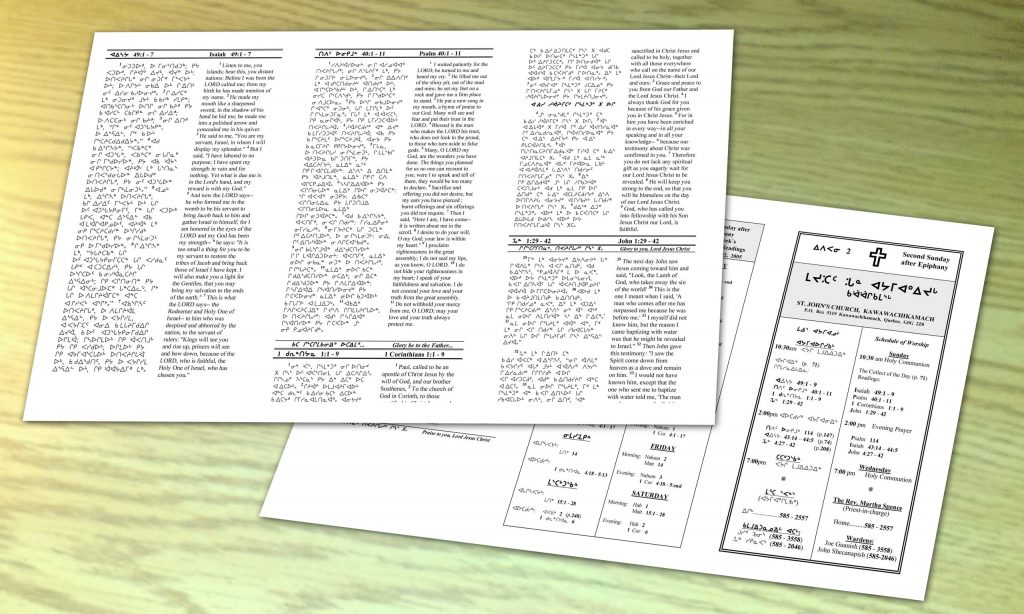

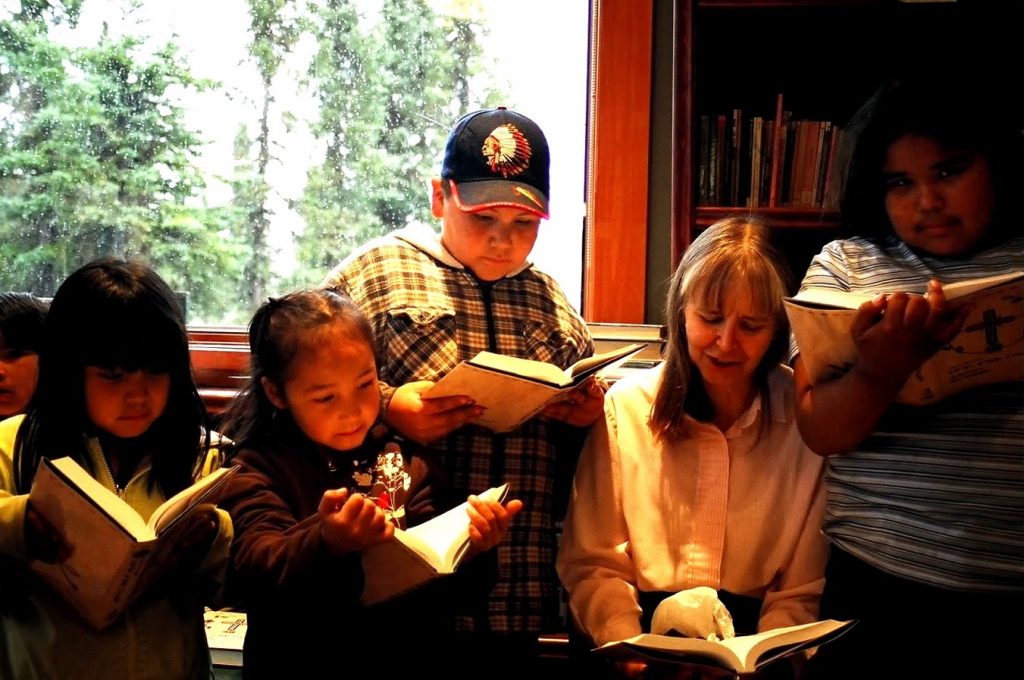

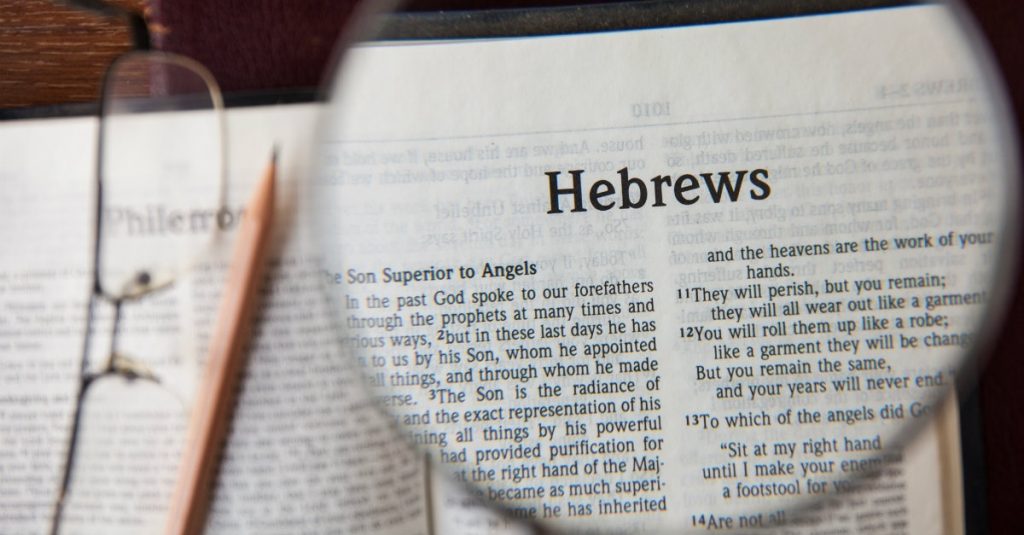

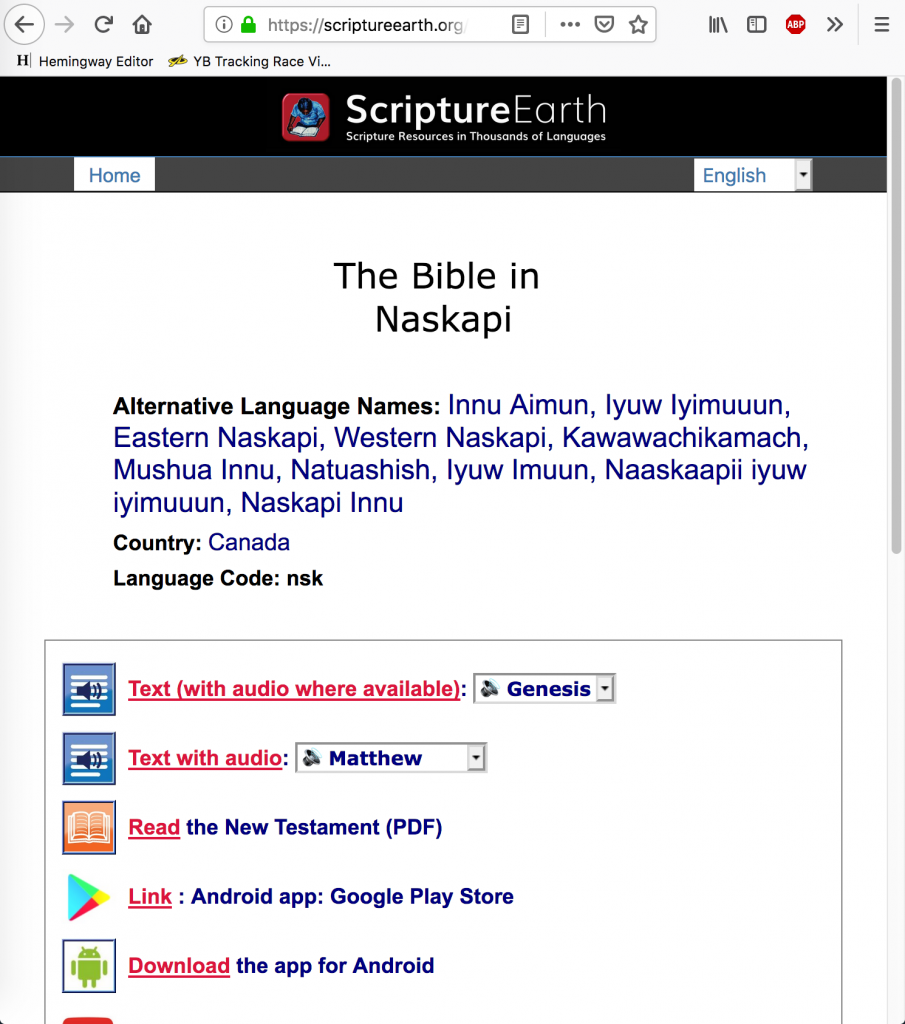

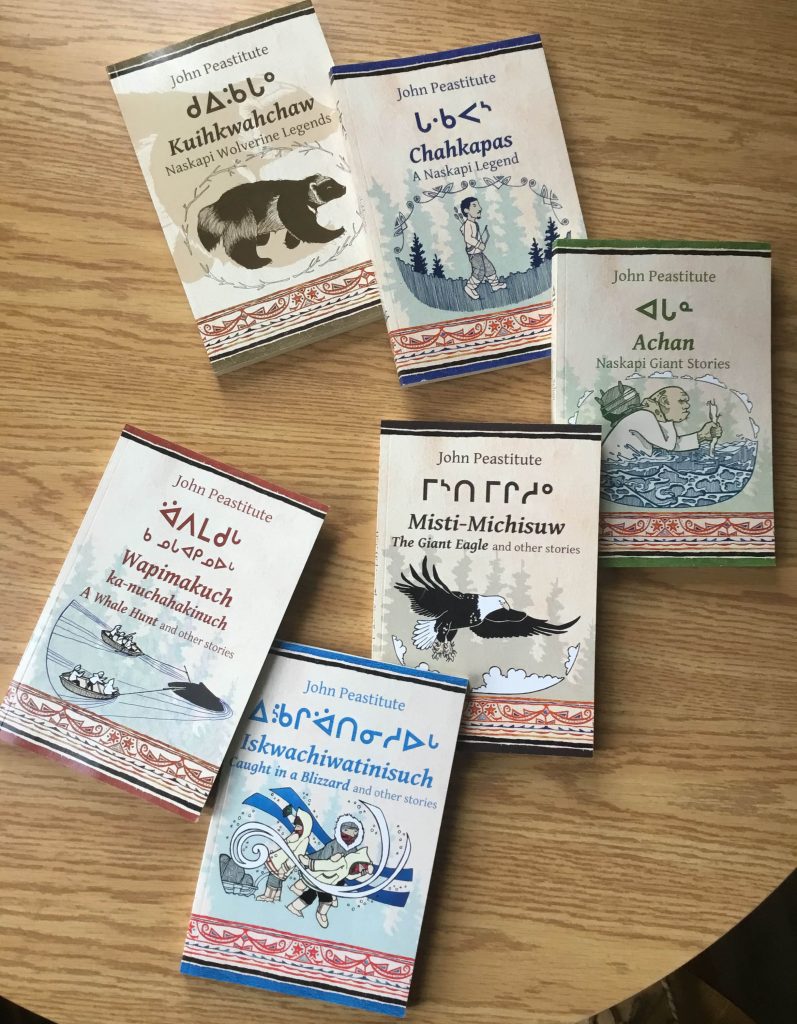

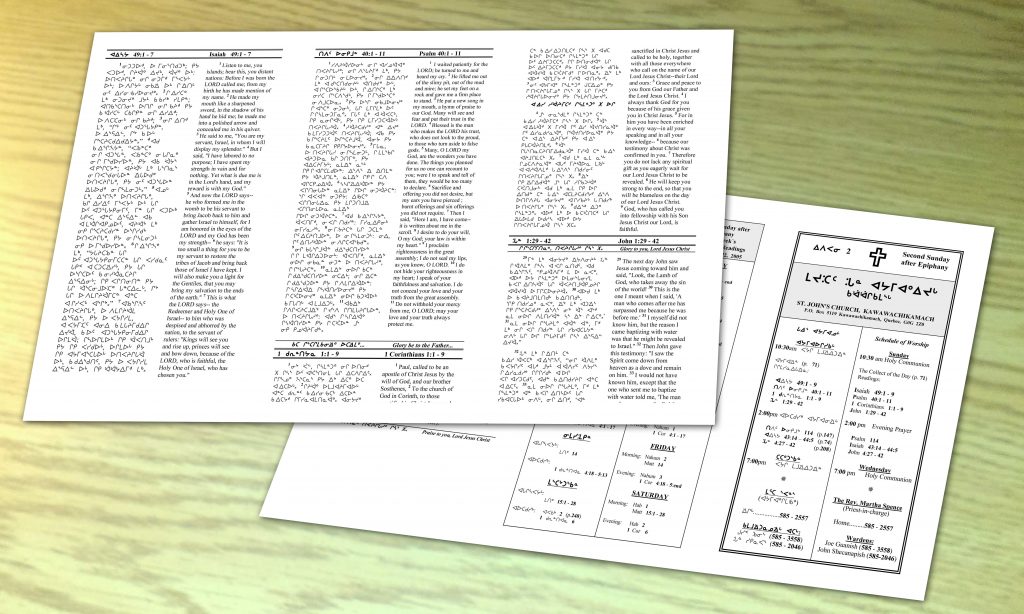

The Naskapi people have been literate in their own language for a little over a century or so, beginning when the Anglican clergy brought Cree Scriptures and other religious materials with them to the trading posts where the Naskapi traded. But they have been oral storytellers for generations. Interest in encouraging a broader base of Naskapi people to be literate in their own language blossomed in the community and in the school in the 1990s, when an initiative was established to make Naskapi the official “language of instruction” for the earliest years of education. By the year 2000, children were learning to read and write in Naskapi by grade 3, and after this they transition into the majority languages for instruction in later school years.

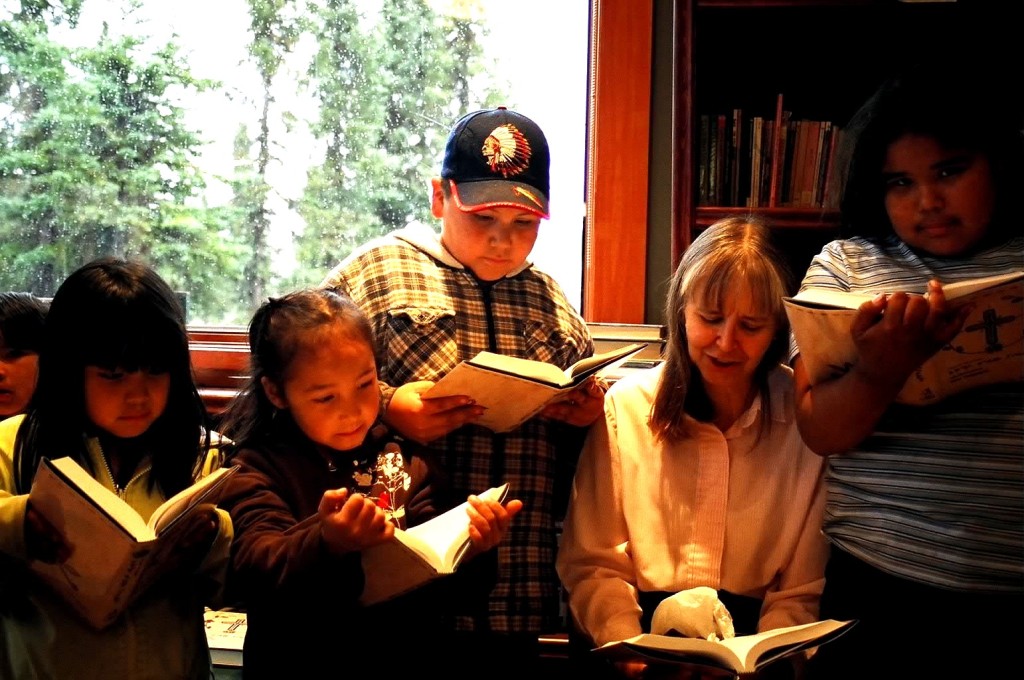

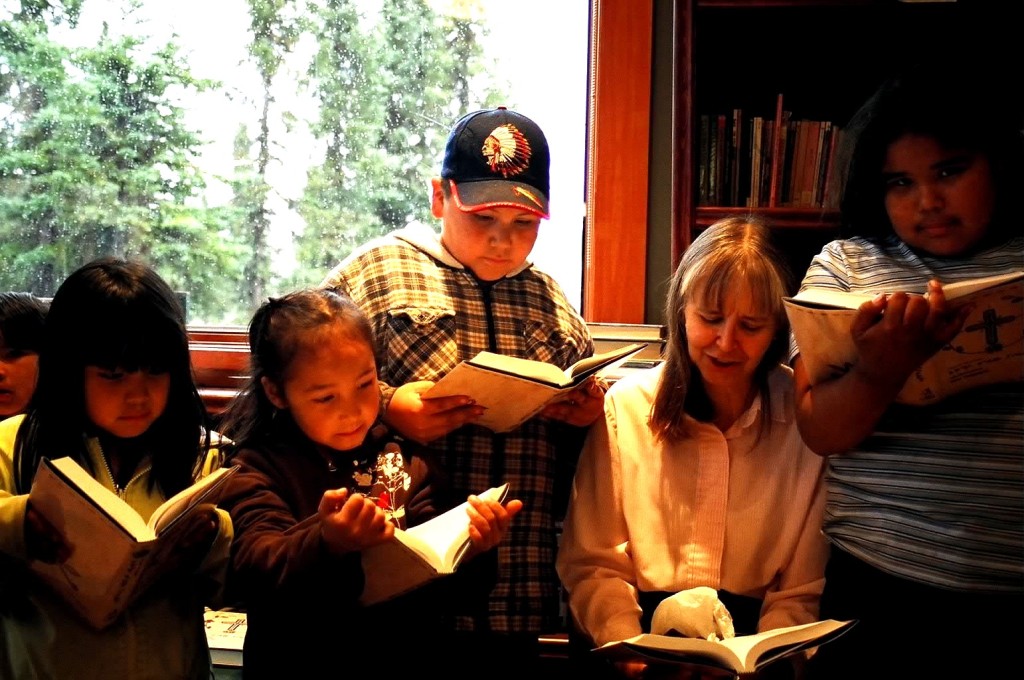

Naskapi children reading with Lana Martens at the Naskapi New Testament Dedication in 2007

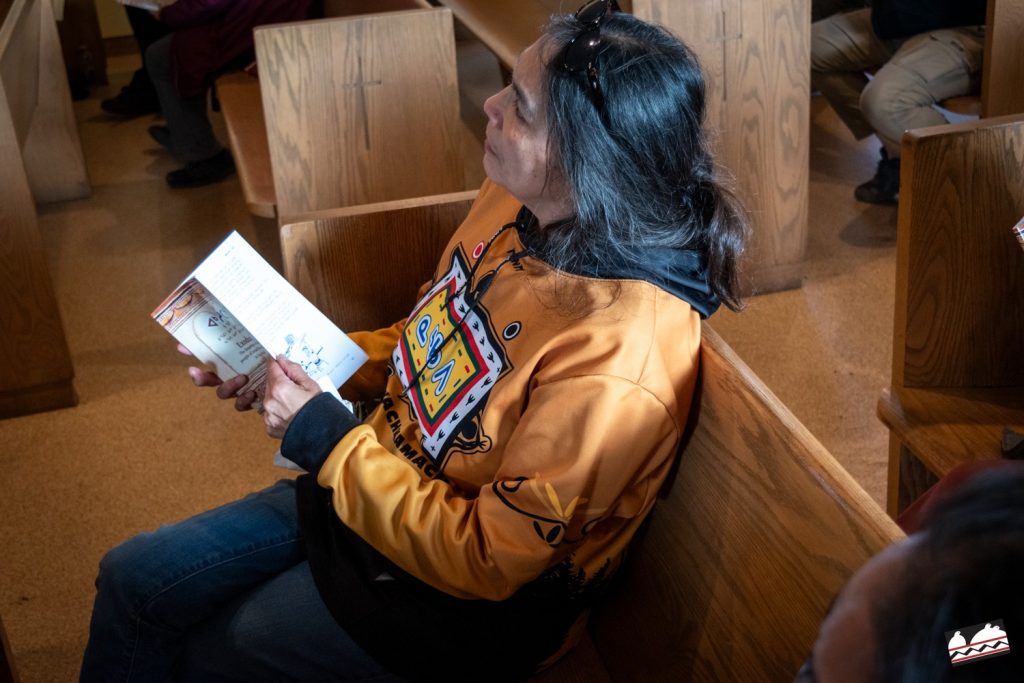

But to develop and maintain literacy, it is imperative that there be a wide selection of material to read in the language. Many items are being translated: from the Bible, hymnals and prayer books at church, to curriculum and other teaching materials at the school. For years, it has also been the standard practice to translate all administrative documents, reports and minutes of meetings held in the community.

The Naskapi Legends and Stories Project

One of the most valuable projects begun by the Naskapi Development Corporation (NDC) was to produce high-quality Naskapi language reading materials in the Naskapi language from the minds and culture of the Naskapi people themselves. This article is about the Naskapi Legends and Stories Project.

One of the most valuable projects begun by the Naskapi Development Corporation (NDC) was to produce high-quality Naskapi language reading materials in the Naskapi language from the minds and culture of the Naskapi people themselves. This article is about the Naskapi Legends and Stories Project.

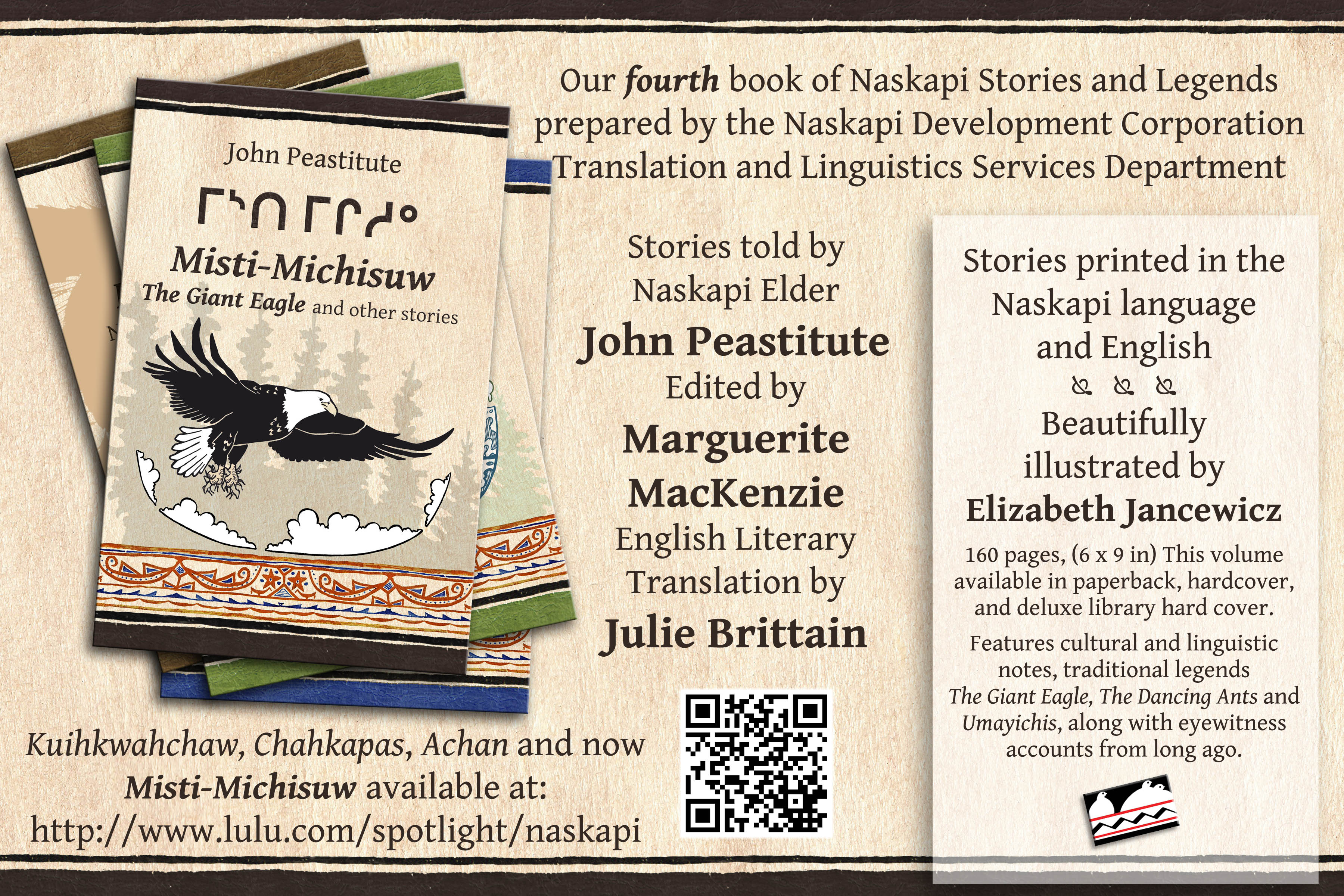

In the summer of 2021, the NDC published their seventh (and final) volume in this project series, Ka-nutachikwayan: When I Hunted Otters and other stories.

The potential for this series of books even before there was a Naskapi Development Corporation; indeed before there was a Naskapi community at Kawawachikamach.

Some Naskapi History

Until the early 20th century, the Naskapi people were a loosely affiliated indigenous people society living in small independent family groups: nomadic caribou hunters whose territory spanned the northern portion of the Quebec-Labrador peninsula. According to Henriksen (2010), the Naskapi probably came together infrequently, perhaps only annually at the peak caribou-hunting season. Until it was closed in 1868, the first principal trading location for the Naskapi was the Petitsikapau post, called Fort Nascopie by the Hudson’s Bay Company, situated on the southern extreme of the traditional Naskapi hunting territories (read an account of this location in the first story in our sixth book, Wapimakuch ka-nuchahakinuch: A Whale Hunt, “Petitsikapau to Chimo”).

Fort Chimo visitors, c.1884 (photo by L.M. Turner)

Following the closure of Fort Nascopie, the Naskapi took their trading business either north to Fort Chimo, near Ungava Bay, or east to the Davis Inlet post, on the Atlantic Ocean; and thus began a process which would eventually lead them to become two separate and sedentary groups. Those who hunted in the northern and north eastern areas of the interior frequented Fort Chimo and Fort McKenzie, and those hunting farther south and east traded at Davis Inlet (Utshimassits). Subsequently, each group would adopt distinct Christian traditions, the Eastern Naskapi (Mushuau Innu) becoming Catholics and the Western Naskapi becoming Anglicans.

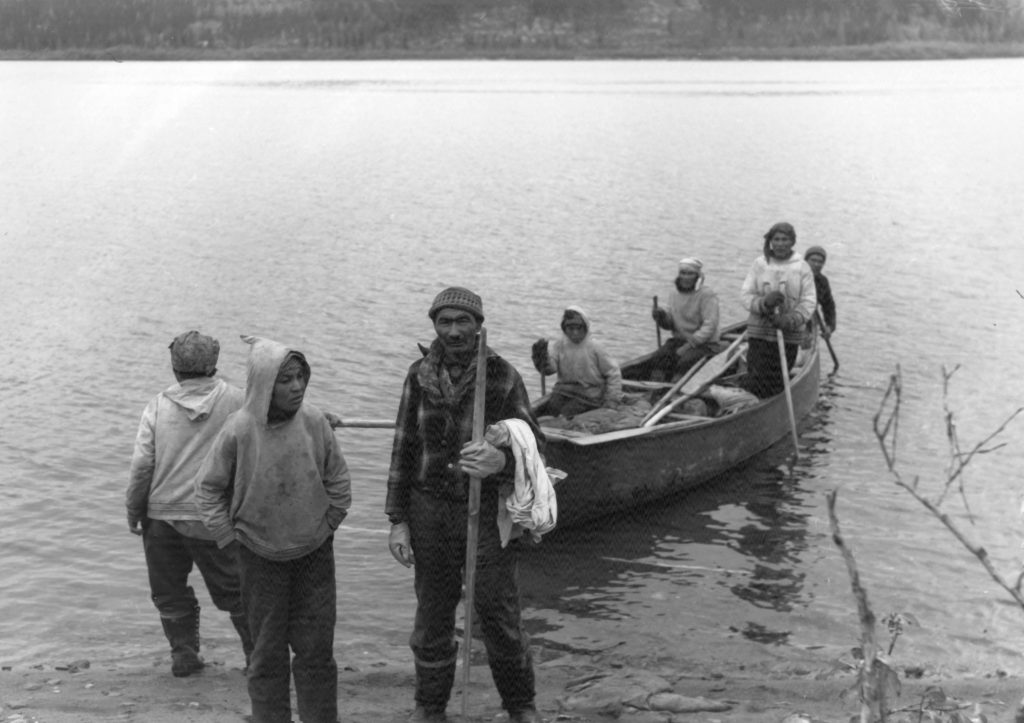

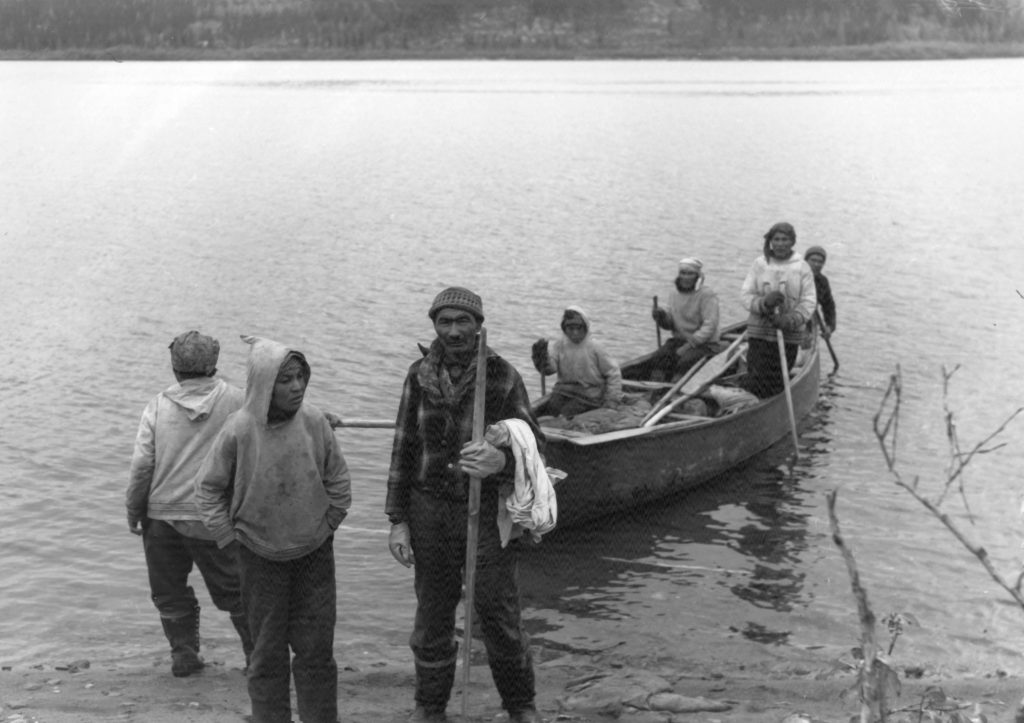

Canoe coming ashore at Fort McKenzie, c.1942 (photo by P. Provencher)

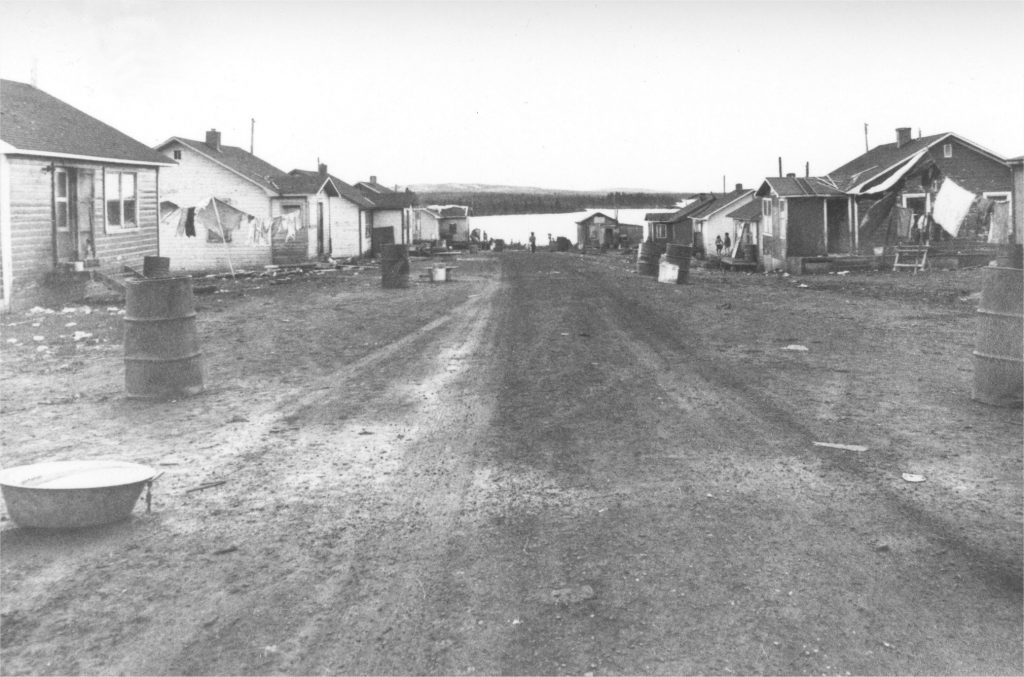

In 1956, the Fort Chimo (Western) Naskapi journeyed south to the mining town of Schefferville where educational and medical facilities, as well as employment opportunities in the recently opened iron ore mines were becoming available (Cooke 2012). A year later they were moved two miles away from the town, to John Lake, where they remained until 1972, along with some Montagnais who had moved to Schefferville from the Sept-Îes area.

It was during this period in John Lake that the stories in this book, along with dozens of other tipâchimûna and âtiyûhkinch were performed by John Peastitute and recorded.

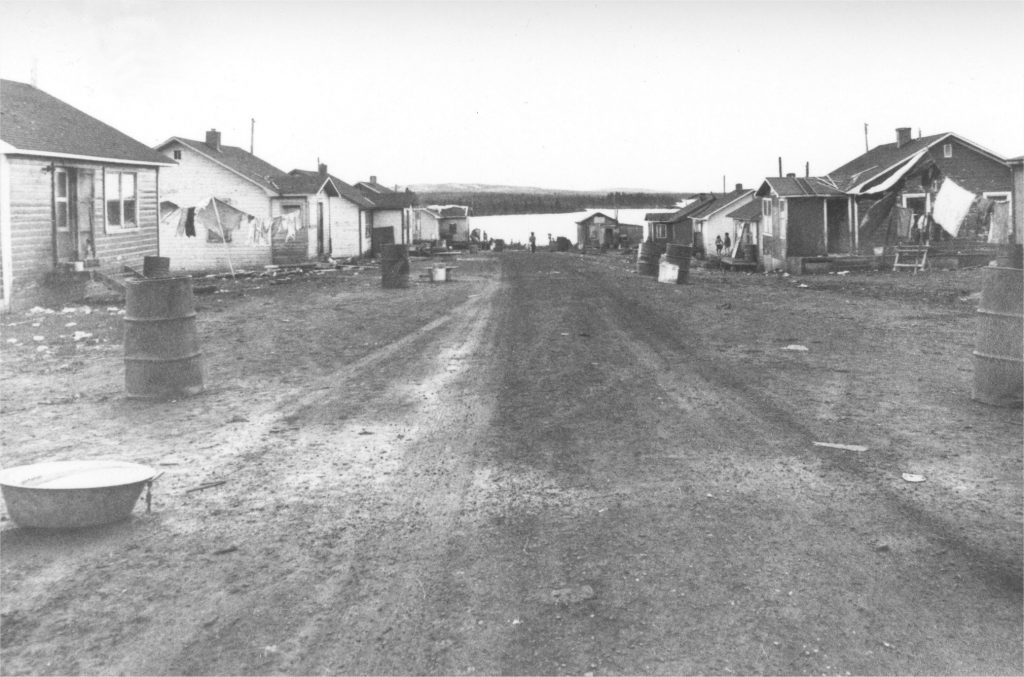

John Lake community, c.1962 (photo by A. Cooke)

Naskapi Storytelling

Like other indigenous peoples, the Naskapi have a long tradition of storytelling, passing histories and legends from generation to generation. And, like other Algonquian-speaking groups, the Naskapi distinguish two main genres of storytelling: tipâchimûn is the word for true adventures or histories in which the storyteller himself or other eyewitnesses are characters in or eyewitnesses to the story, and âtiyûhkin is the word for stories which are from a distant “time before now”, generally referred to as “legends”, and often include animal characters.

It may be simple to say that the difference is merely that tipâchimûna (plural form of tipâchimûn) are “only” historical accounts while âtiyûhkinch (plural form of âtiyûhkin) are “only” myths or legends (Ellis 1988). But in truth the dichotomy goes much deeper than this. Tipâchimûna may and often do contain fantastic, amazing or unbelievable accounts—but âtiyûhkinch follow a strict and ancient narrative formula. Savard (1974) calls them “that which must be conveyed”. In his treatise on the Wolverine stories he says that the storyteller he worked with would never have considered the idea that someone could invent a new âtiyûhkin. These stories can only be transmitted from one storyteller to another.

John Peastitute

John Peastitute (1896-1981) was a Naskapi elder who was not only well respected as a story-keeper, but also an accomplished storyteller. His repertoire of both tipâchimûna and âtiyûhkinch was extensive, and his performances engaging. The tapes of his stories that have survived to be processed and studied are a precious legacy.

John Peastitute with his wife Susie Annie, near Fort McKenzie c.1942 (photo by P. Provencher)

While he knew best the area north and northwest of Fort McKenzie, where he hunted and lived most of his adult life, John traveled during his lifetime virtually everywhere in traditional Naskapi territory and then some. Before settling at Schefferville, John had trecked even beyond traditional Naskapi territory as far as Sept-Îles (Uashat), North West River (Sheshatshit), Davis Inlet (Utshimassits) and Great Whale River (Whapmagoostui) places where some of his relatives would take their trade and eventually settle. You can read an engaging account of one of these journeys in the seventh book of this series, Ka-nutachikwayan: When I Hunted Otters, “A Journey East”.

John himself settled with his family in the Schefferville area in the 1950s with the rest of the Naskapi community.

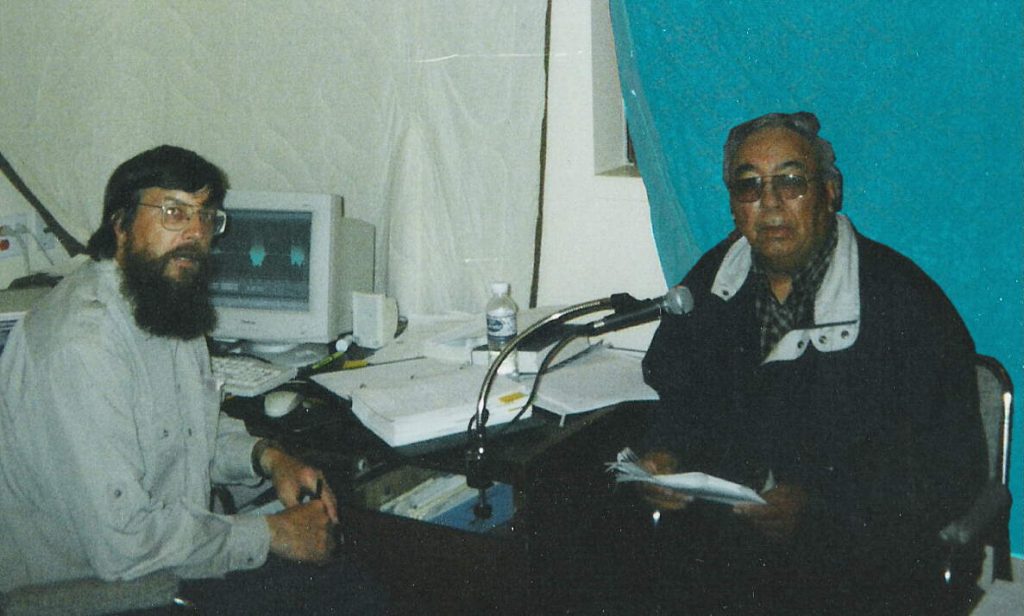

Recording the stories

In 1967 and 1968, when John was in his 70s, Serge Melançon visited the John Lake community near Schefferville to record traditional indigenous stories on audio tape. He was working with the Laboratoire d’anthropologie amérindienne under the supervision of Rémi Savard, on a project to collect oral traditions of several Quebec groups and to compare the content and style of the similar stories across linguistic and cultural boundaries. Savard’s book Carcajou et le sens du monde: récits Montagnais-Naskapi is one of the results of that project, and interested readers would do well to consult it for a thorough cultural analysis some of these and the other stories told by several First Nations in Quebec. (This book is written in French; the title in English is: Wolverine and the Sense of the World: Montagnais-Naskapi Stories, Savard 1971.)

Cover of Savard’s book

The collection of Innu and Naskapi tapes that were originally collected by Savard’s project remained the property of the Laboratoire, but copies on cassette tape were later released to linguists for eventual transcription. Many of the Sheshatshiu Innu (of Labrador) stories from this project are available on the innu-aimun.ca website, and as printed books (Lefebvre, Lanari and Mailhot 1999).

Following the completion of Savard’s project, copies of the Naskapi tapes, along with photocopies of some of the transcriptions, were placed at the NDC office, which was located in Schefferville at the time.

In the course of our compilation of the Naskapi Lexicon, the NDC Board decided to also take on the task of transcribing and translating the stories as a cultural development project.

From Tapes to Books

In the early 1990s, I (Bill) was invited to work alongside the Naskapi translators working at the NDC office in Schefferville on the Naskapi Lexicon, and to help facilitate their other language development projects. During August and September of 1994, I listened to all the tapes and compared the content with the pages and pages of documentation that came with them, and then produced an inventory of all the stories, their (presumed) titles, their position in the audio collection, and I catalogued all of the associated documentation.

With my help, NDC translators Phil Einish and (the late) Thomas Sandy read and annotated the photocopied material. Some of this material had been typed, some handwritten. Some were photocopies of Melançon’s or other’s field notes, and some were preliminary transcriptions of the tapes made by (the late) Elijah Einish in the early 1980s. Some of the photocopied pages had been keyboarded by Dr. Marguerite MacKenzie or one of her students at Memorial University in the late 1980s.

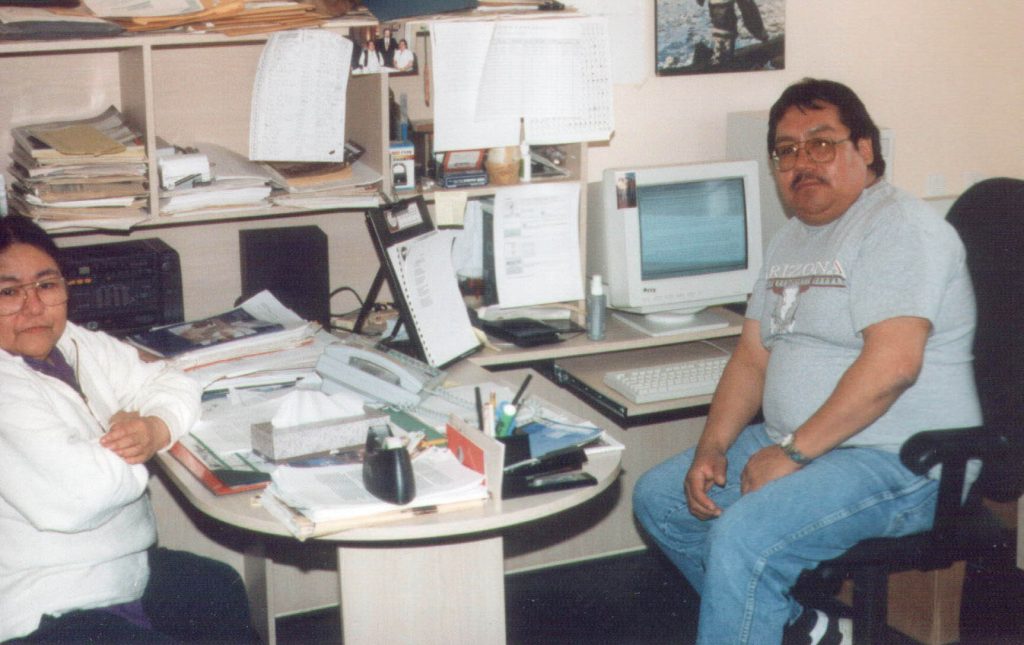

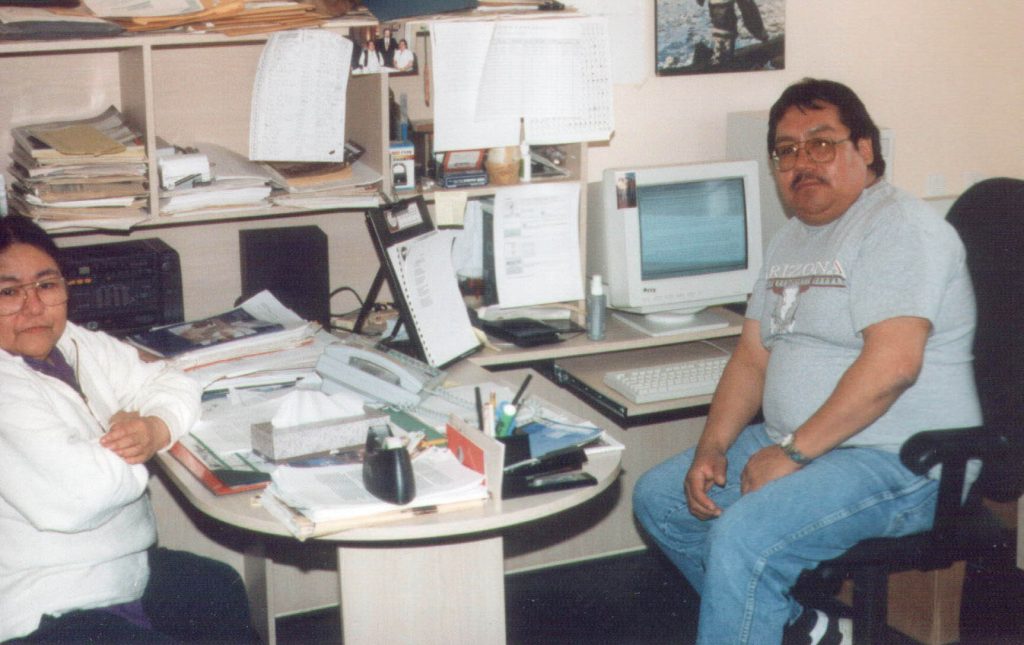

Alma & Phil at work (1999)

In the late 1990s, the Naskapi Legends and Stories Project goals were set down, and it was decided that it was necessary for each recording to be carefully reviewed phrase by phrase by the Naskapi translation team and the linguistics consulting team, and thoroughly transcribe the text in Naskapi. At that time, the team was made up Naskapi translators Silas Nabinicaboo, Philip Einish and Alma Chemaganish, and consultant linguists Dr. Marguerite MacKenzie, Dr. Julie Brittain, and myself serving as the project’s faciliator and coordinator.

Literary translation process

While our primary goal has always been to render the stories into the Naskapi writing system so that they would be accessible as literature for current Naskapi readers in Kawawachikamach, a secondary goal has been to reproduce in English the elegance and stylistic skill employed by the storyteller, while remaining as faithful as possible to the original text.

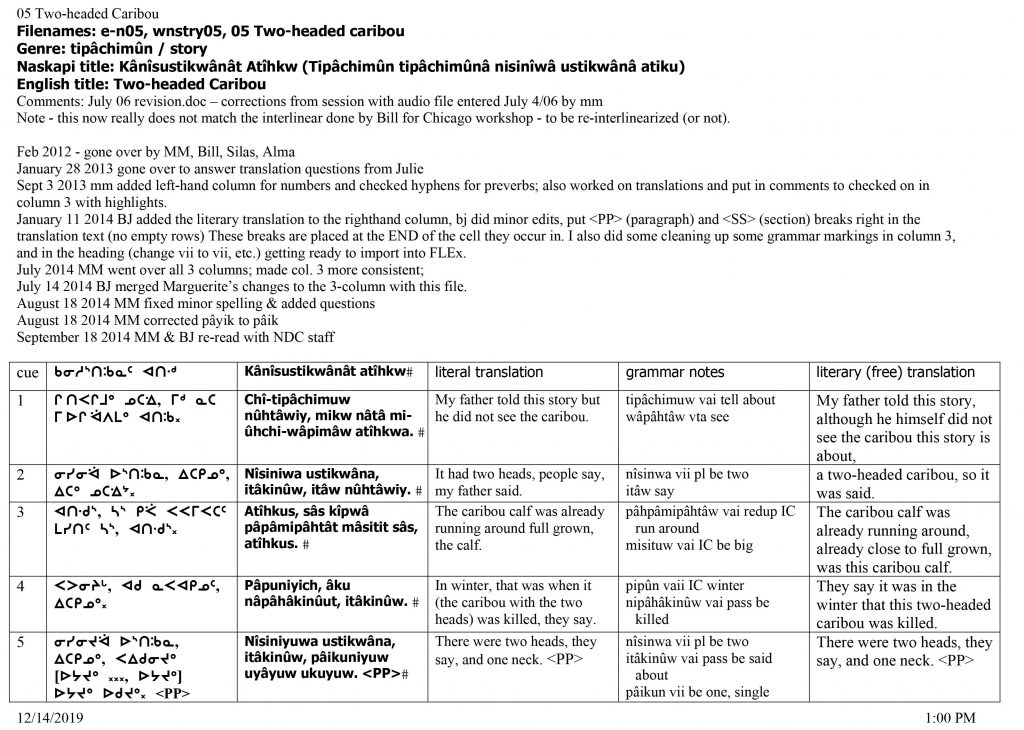

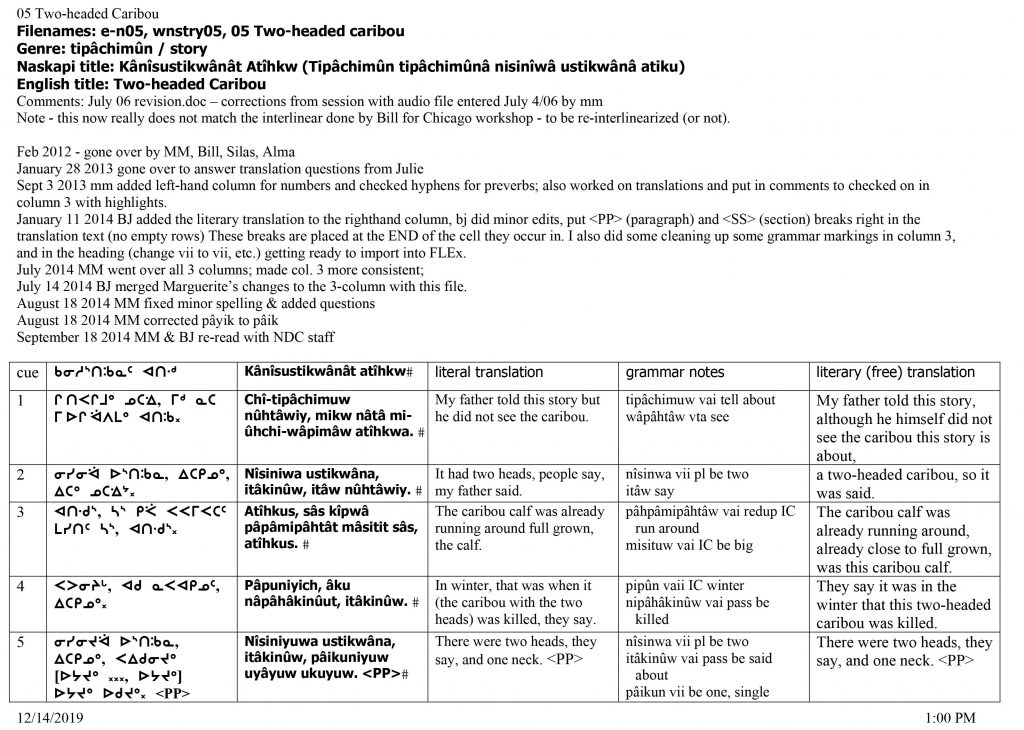

The translation process we eventually adopted involved several stages. In group sessions the digital audio file of each story was listened to line-by-line, while the Naskapi team followed along reading a transcribed version in syllabics, which was projected on a screen for the group to see. Each word of the transcription was verified for accuracy and faithfulness to the performance, and translated into a fairly literal rendering in English. Further, each verb was parsed for its inflectional morphology, and the Naskapi team provided information about accurate translation, natural expression, and cultural matters.

Story review and translation session with Dr. Marguerite MacKenzie and the Naskapi team (2014).

As each story is thus meticulously annotated, reviewed and corrected, careful notes are taken and maintained by Dr. Marguerite MacKenzie with the transcription and translation.

Dr. MacKenzie has served as professor and head of the Department of Linguistics at Memorial University, Newfoundland, and has spent her career working with speakers of Cree, Innu (Montagnais) and Naskapi on dictionaries, grammars, and language training materials. She is co-editor of the East Cree Lexicon: Eastern James Bay Dialects (2004, 2012), the Naskapi Lexicon (1994) and the English and French versions of the Innu Lexicon (2013).

These notes were then turned over to Dr. Julie Brittain at Memorial University in Newfoundland, a specialist in Algonquian syntax as well as a gifted English translator of the Naskapi text, with the ability to capture not only the meaning of the original story, but able to also communicate something of the style of the story based on her study of Naskapi language structures. If any questions arise during this stage, these questions are once again reviewed and answered by the Naskapi team at Kawawachikamach before the text is ready for the formatting and typesetting stage. This is followed by commissioning illustrations and designing the publication, after which a proof copy is provided to the editors and the translation team.

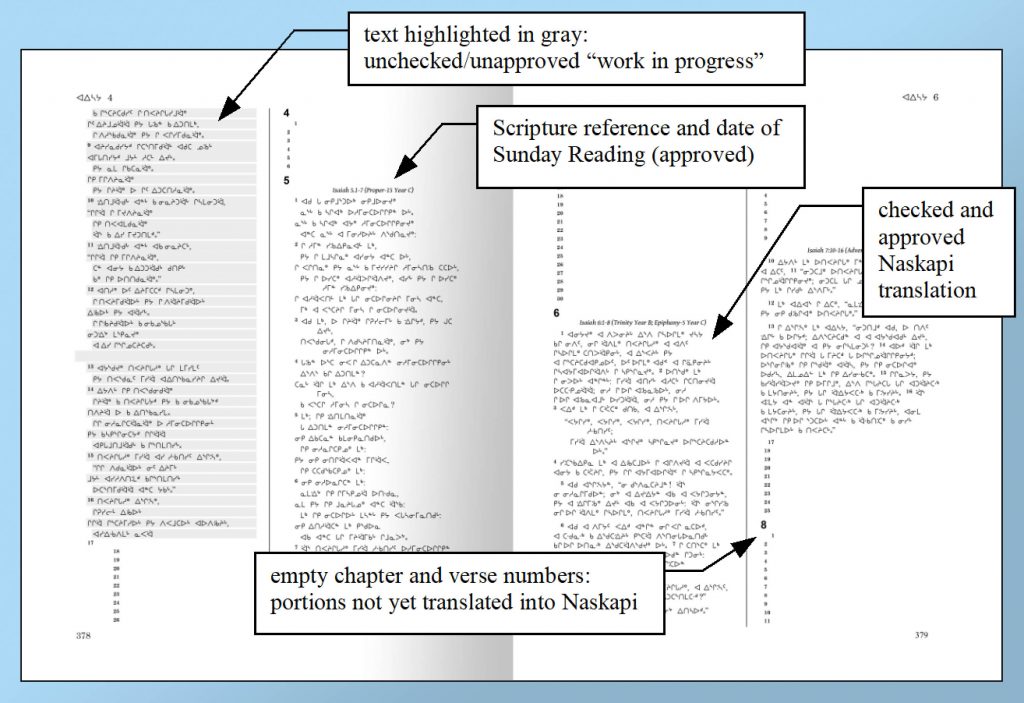

Typical working story analysis sheet used by the Naskapi team and linguists

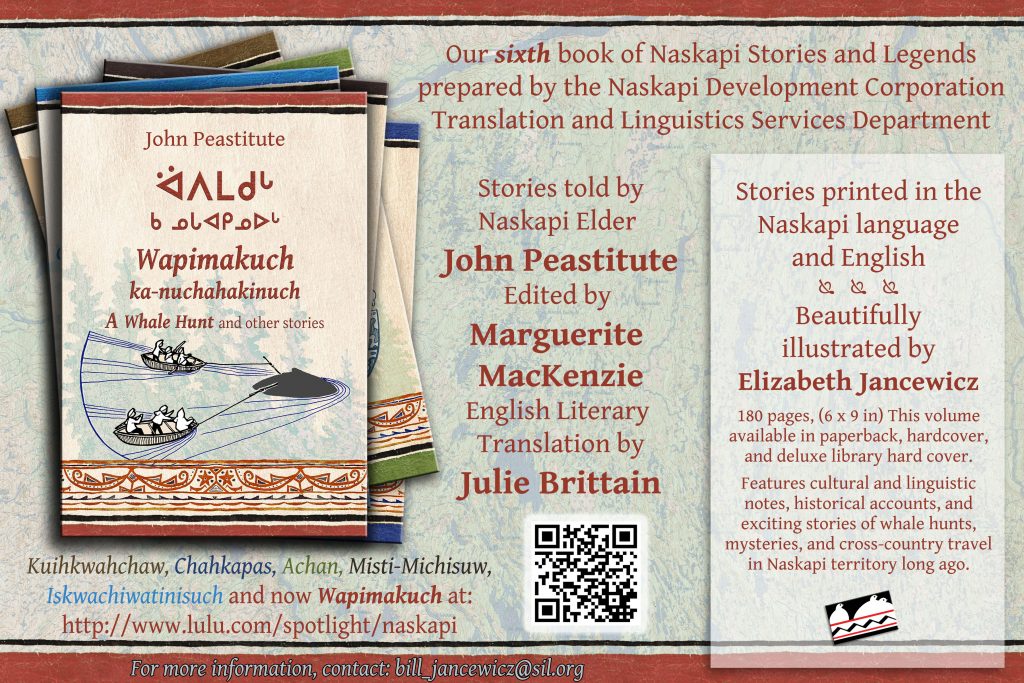

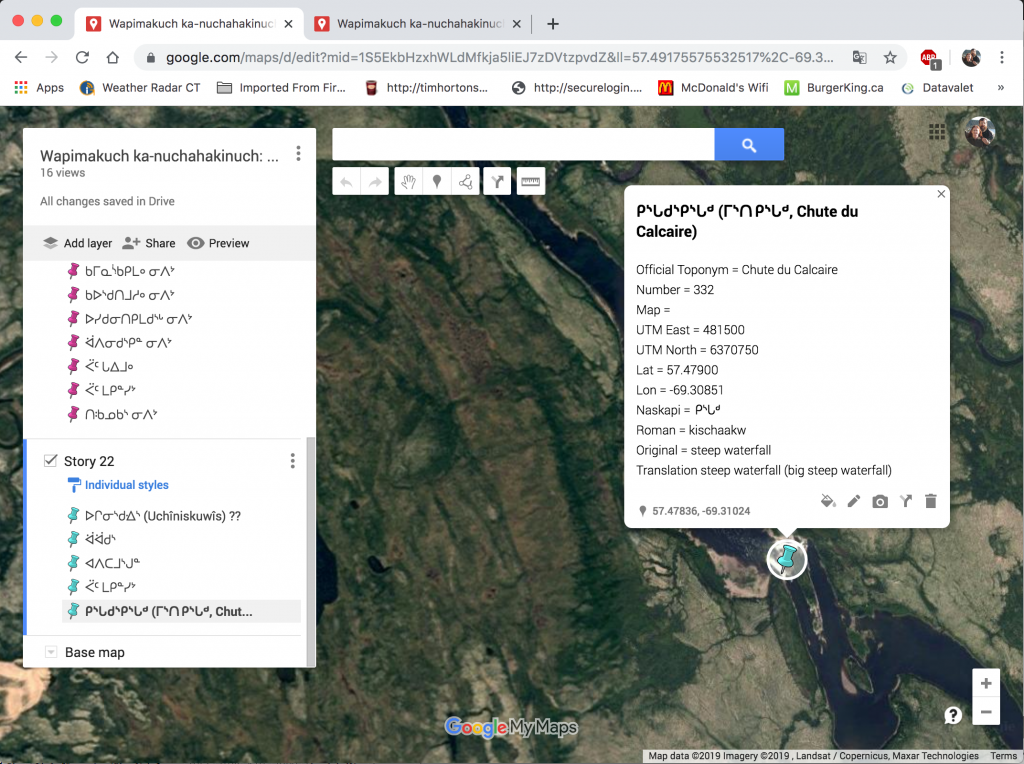

The John Peastitute story series

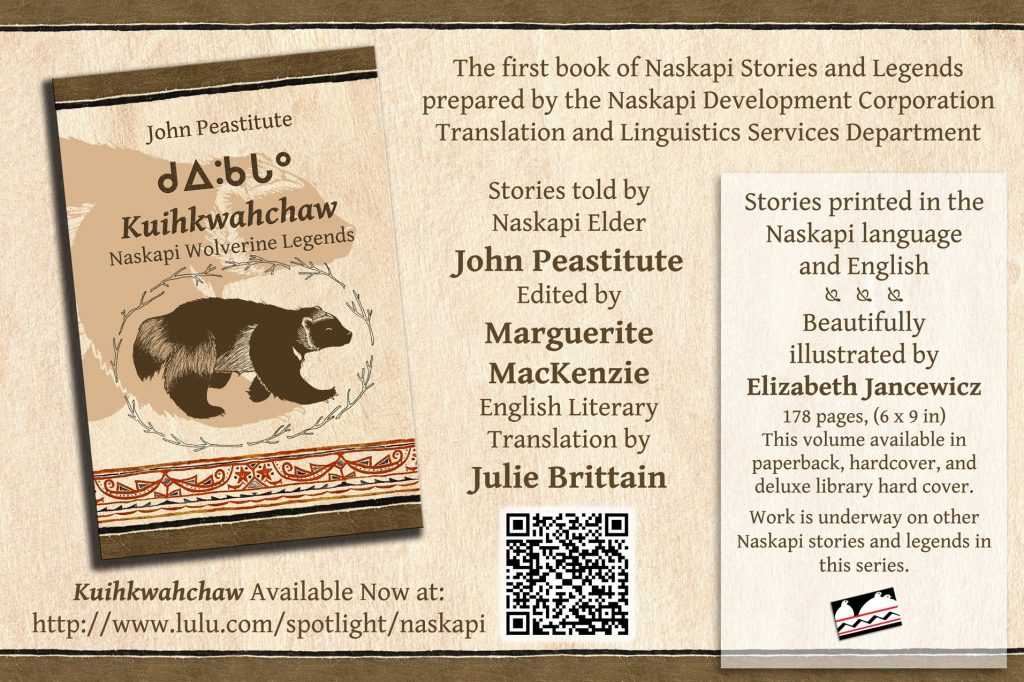

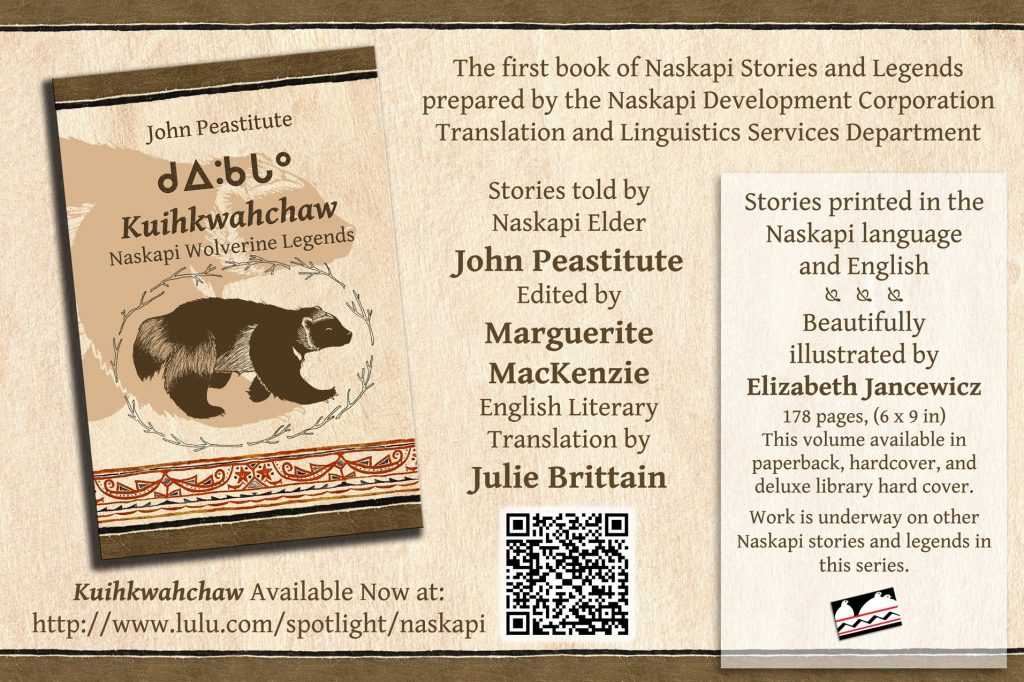

The present goal is to produce topical collections of stories from John Peastitute’s 1967 recordings, during which he told 36 different stories. The team decided to begin with the traditional legends, the âtiyûhkinch, first. John told a series of several stories that had a wolverine as their main protaganist, which fall into the category of Algonquian “trickster” legends. So we decided to do all the wolverine stories as our first volume, which was published in 2013.

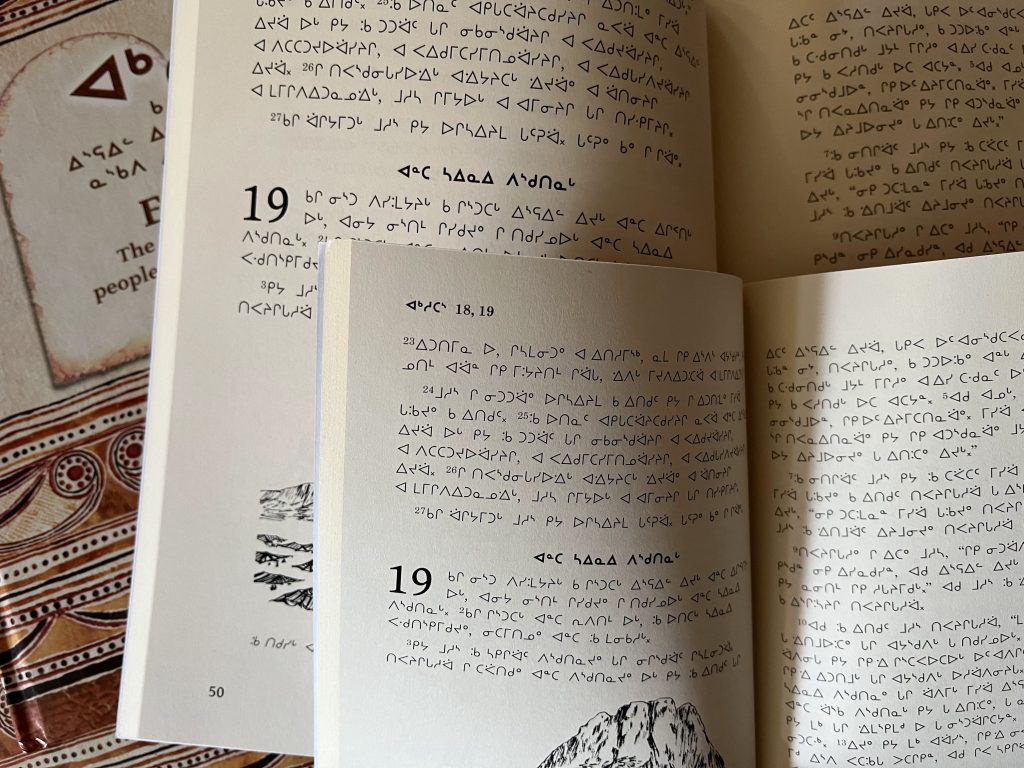

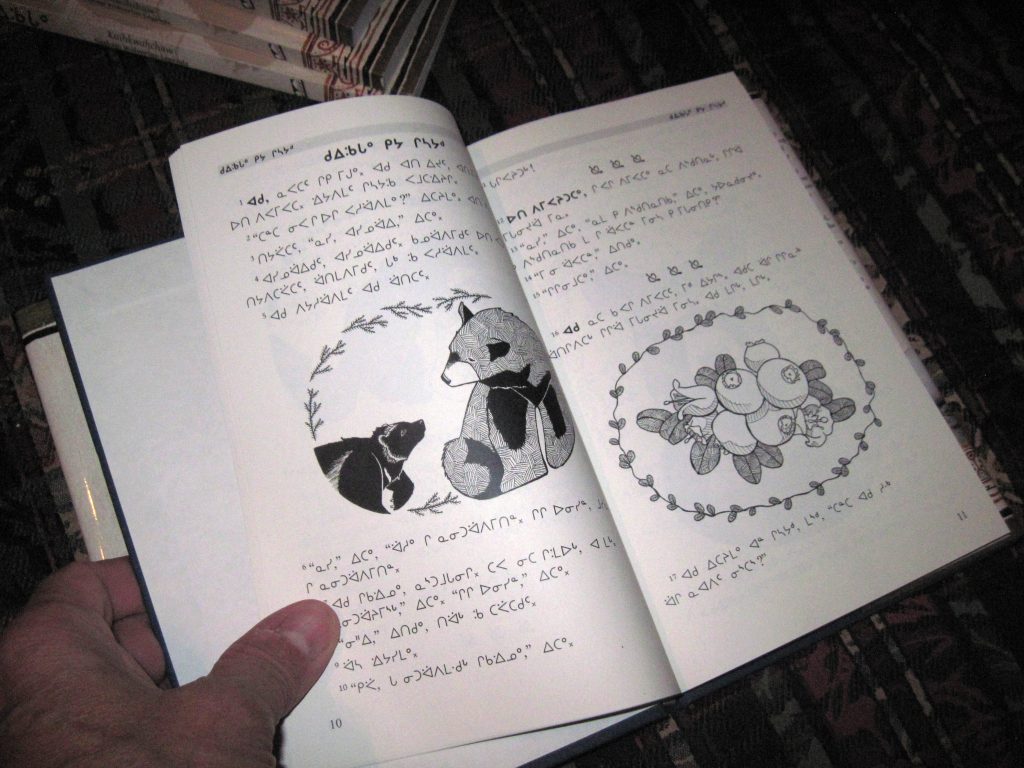

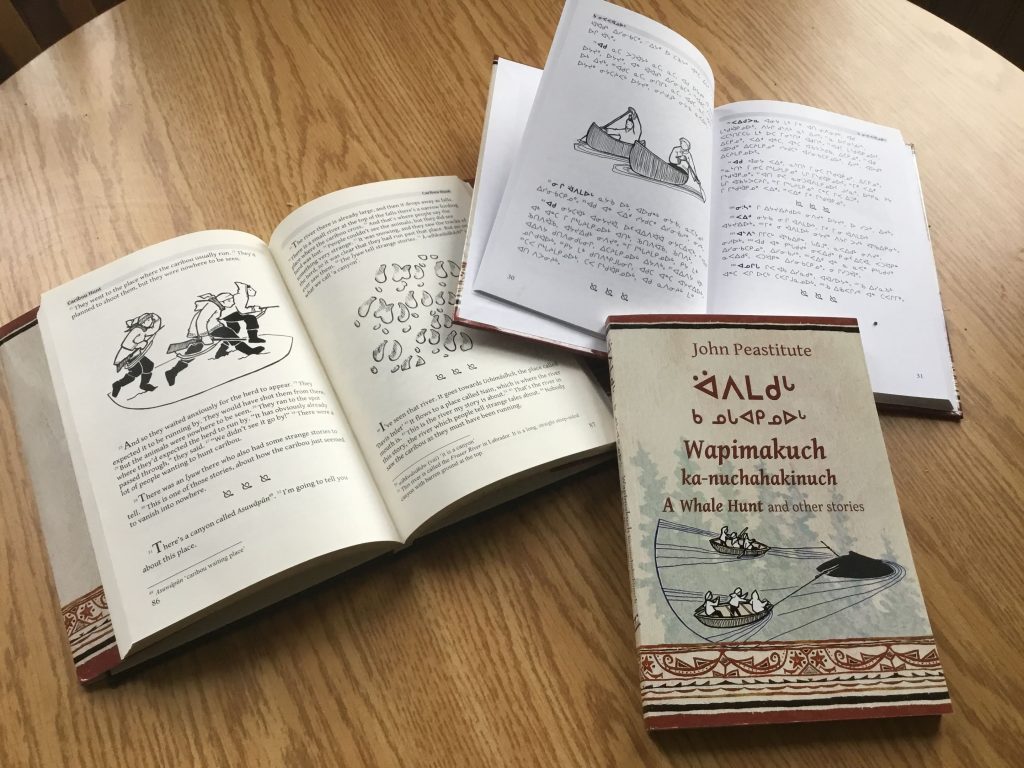

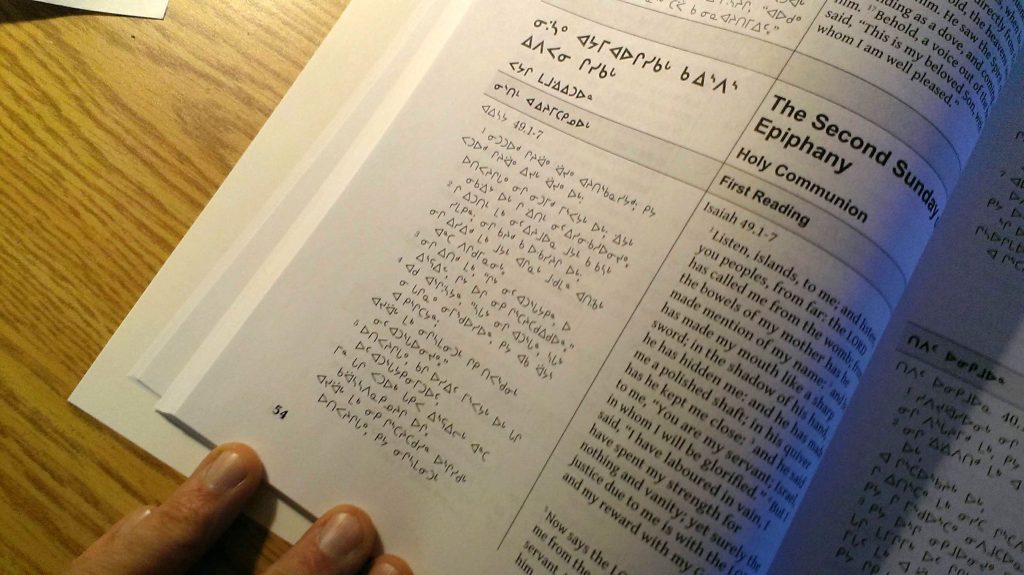

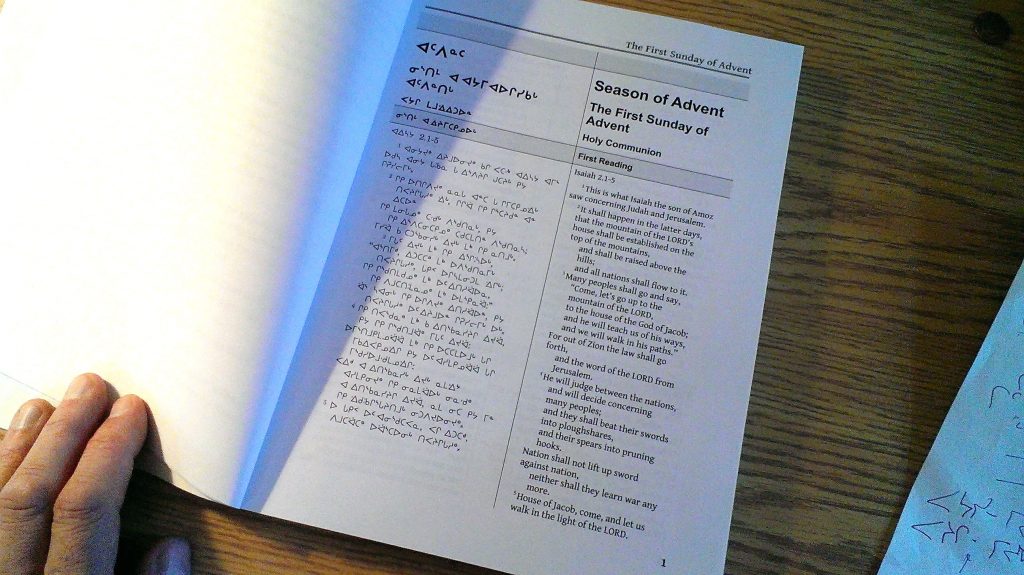

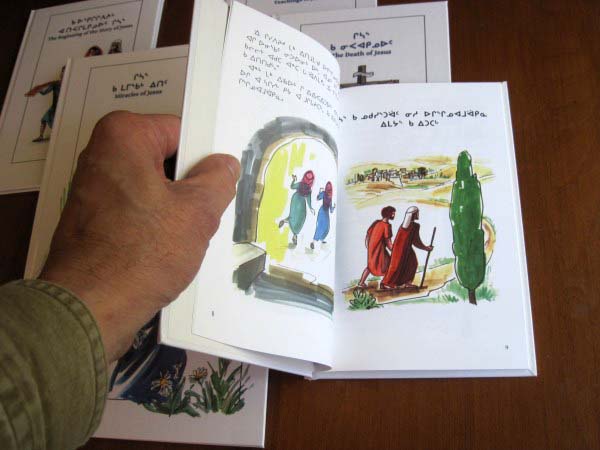

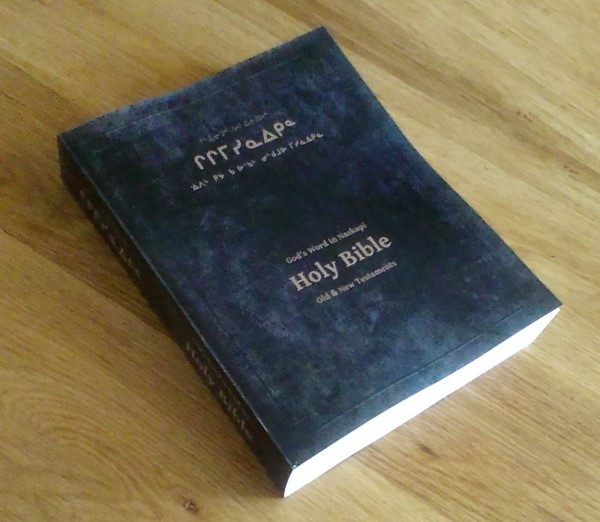

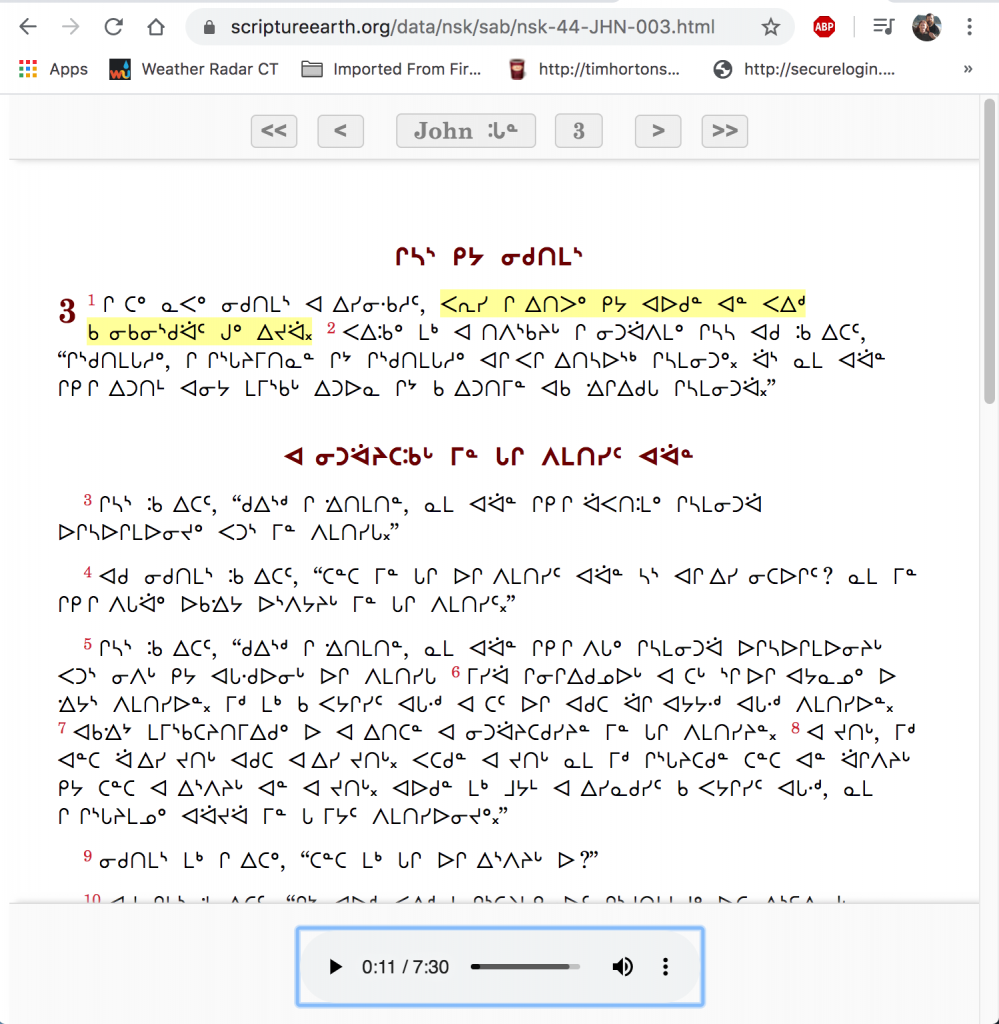

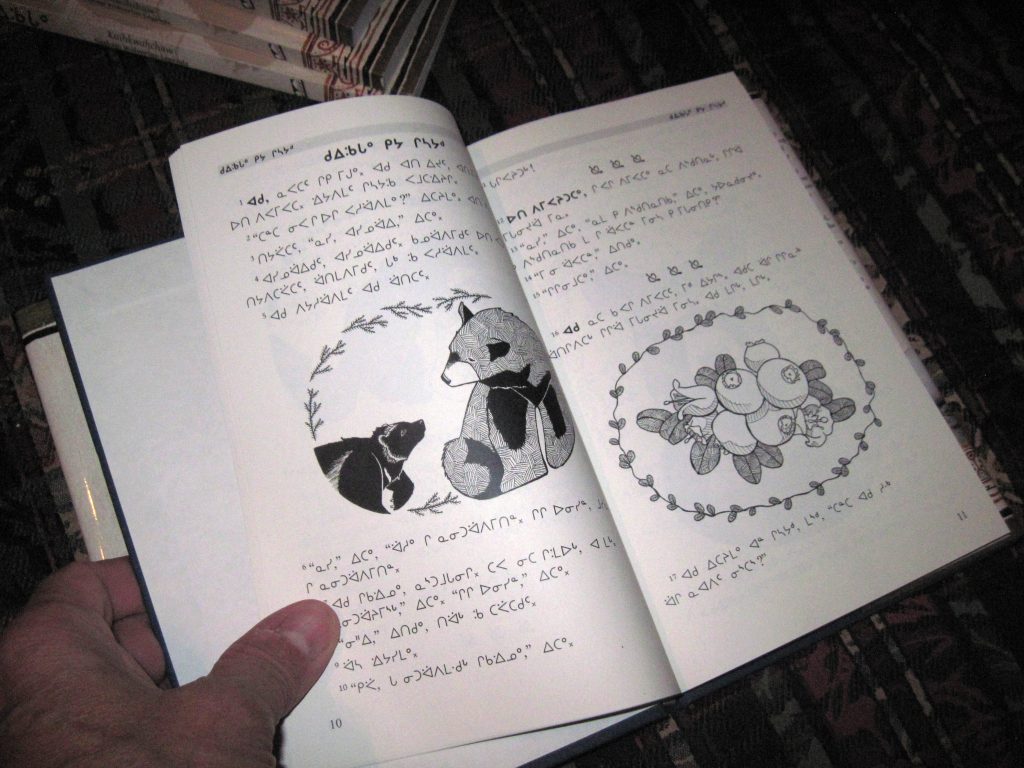

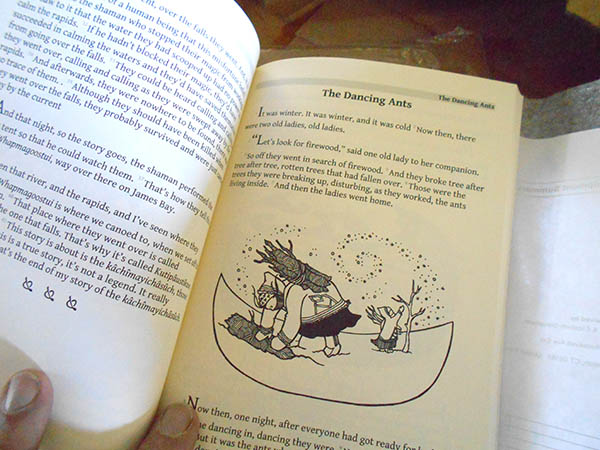

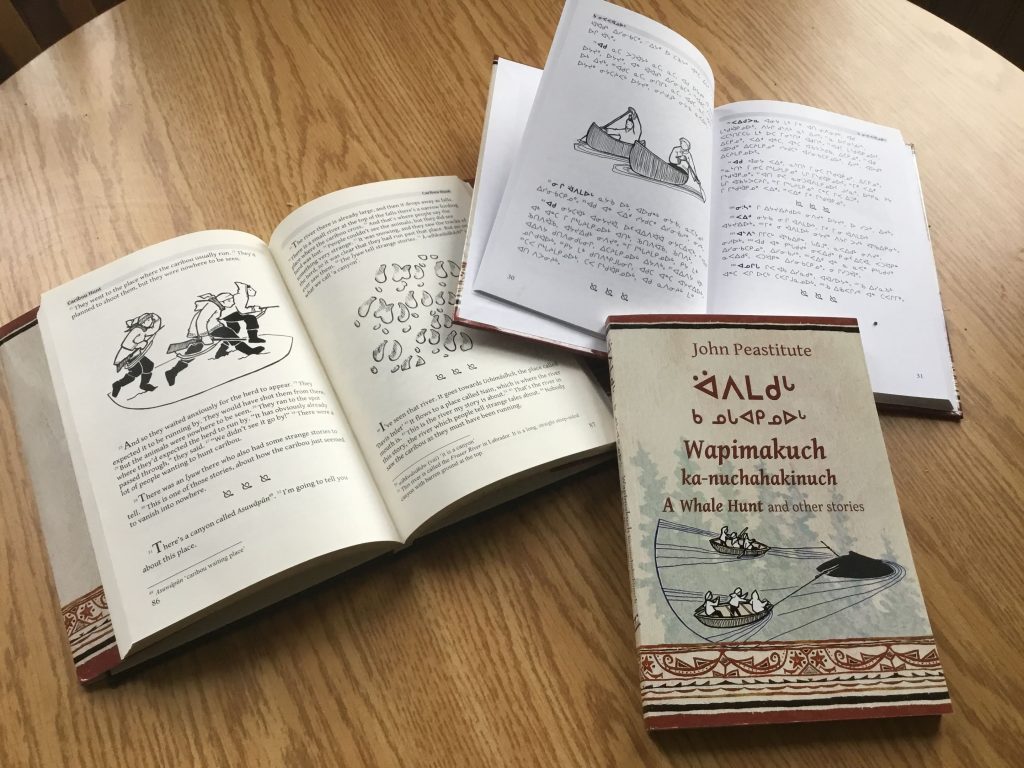

Each volume in the series is organized into four major sections. First, there is the original Naskapi story, written in the Naskapi language for Naskapi readers. This section is printed in a clear, large-size type, paragraphed and formatted with section headings and hand-drawn illustrations.

Each volume in the series is organized into four major sections. First, there is the original Naskapi story, written in the Naskapi language for Naskapi readers. This section is printed in a clear, large-size type, paragraphed and formatted with section headings and hand-drawn illustrations.

The Naskapi Development Corporation commissioned our daughter, Elizabeth Jancewicz, to produce the illustrations. This was a natural project for Elizabeth since she grew up in the Naskapi community of Kawawachikamach and Schefferville, arriving with us there when she was only one year old.

After attending the Naskapi school, Elizabeth studied art at Norwich Free Academy in Connecticut and Houghton College in New York. She returned to the Naskapi community in 2010 to teach art to Naskapi children at the Naskapi school. Today she serves as the visual arts component of the creative team in the touring band Pocket Vinyl. She continues work full time as a professional artist and illustrator, providing beautiful and culturally appropriate work to accompany this series. She also has a growing portfolio of books, graphic novels and commissions. (www.pocketvinyl.com).

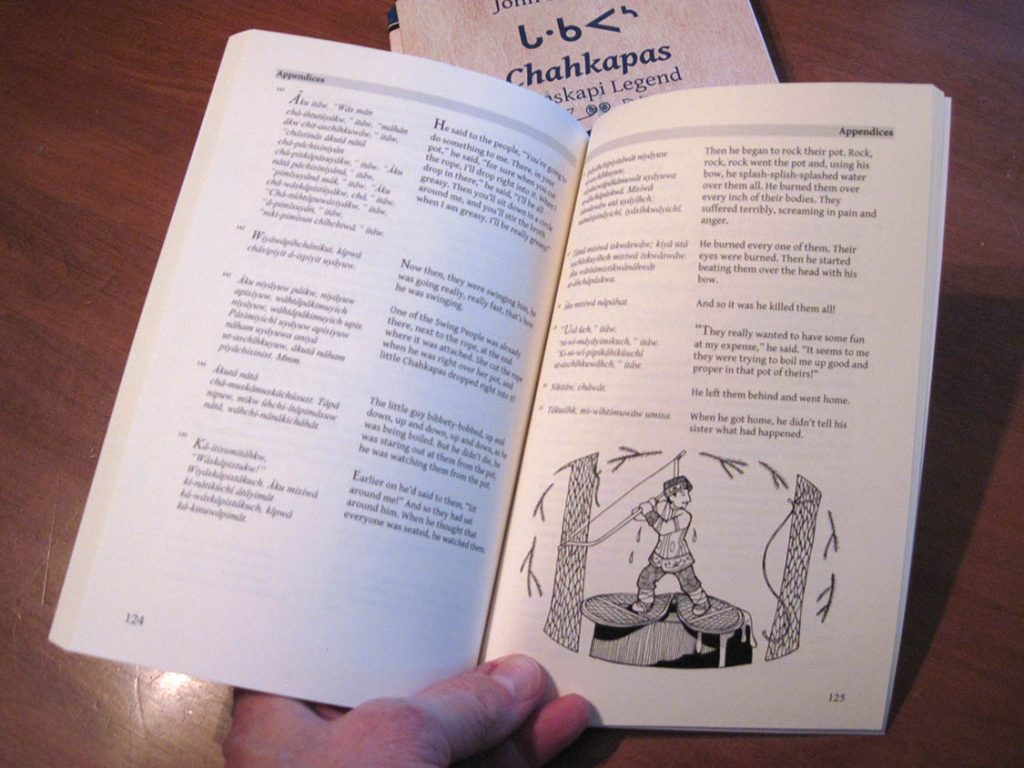

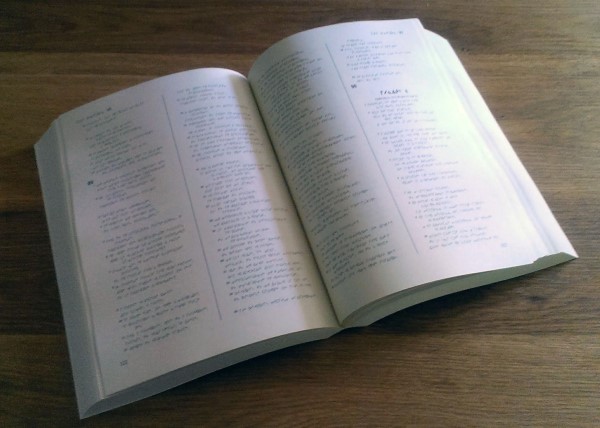

The Naskapi reading section of the Wolverine book

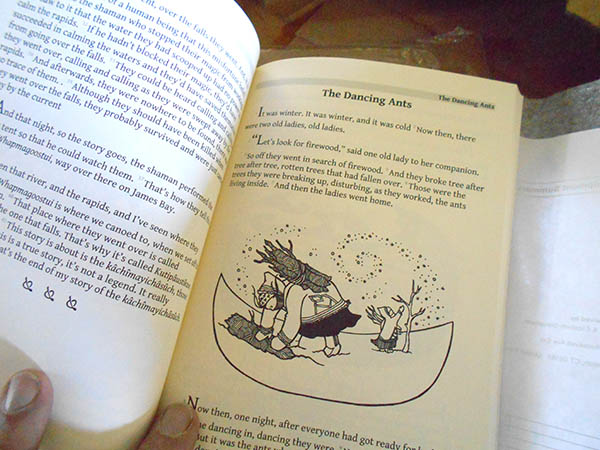

The second section in the books contains the literary English translation, based on the work of the Naskapi team and the consultant linguists, but crafted and rendered in a literary style designed to reflect the Naskapi storyteller’s craft. This translation is prepared by Dr. Julie Brittain.

Dr. Brittain currently works as an associate professor in the Department of Linguistics at Memorial University, Newfoundland. She began research on the dialect of Naskapi spoken at Kawawachikamach in 1996 and continues to work on this and related dialects. She is the author of The Morphosyntax of the Algonquian Conjunct Verb: A Minimalist Approach (2001) and has written numerous articles on the structure of Cree, Innu-aimun and Naskapi.

English translation section from the Giant Eagle book

The third section of the books contains background information about the culture and history of the Naskapi people, along with an in-depth discussion of some of the content of the stories that might be relevant to better understanding. This third section also contains academic bibliographic references to guide the interested reader to resources for further reading (see the links and bibliography at the bottom of this article to see for yourself).

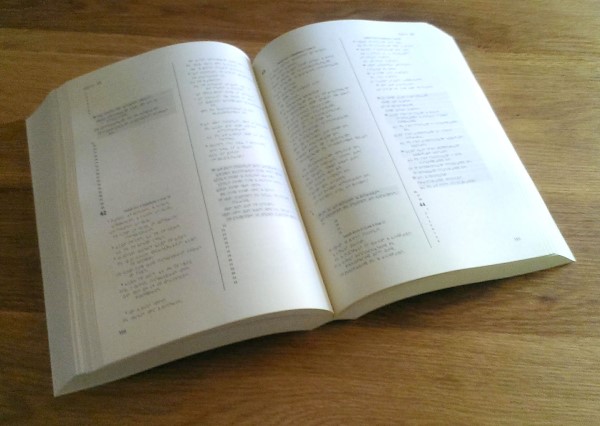

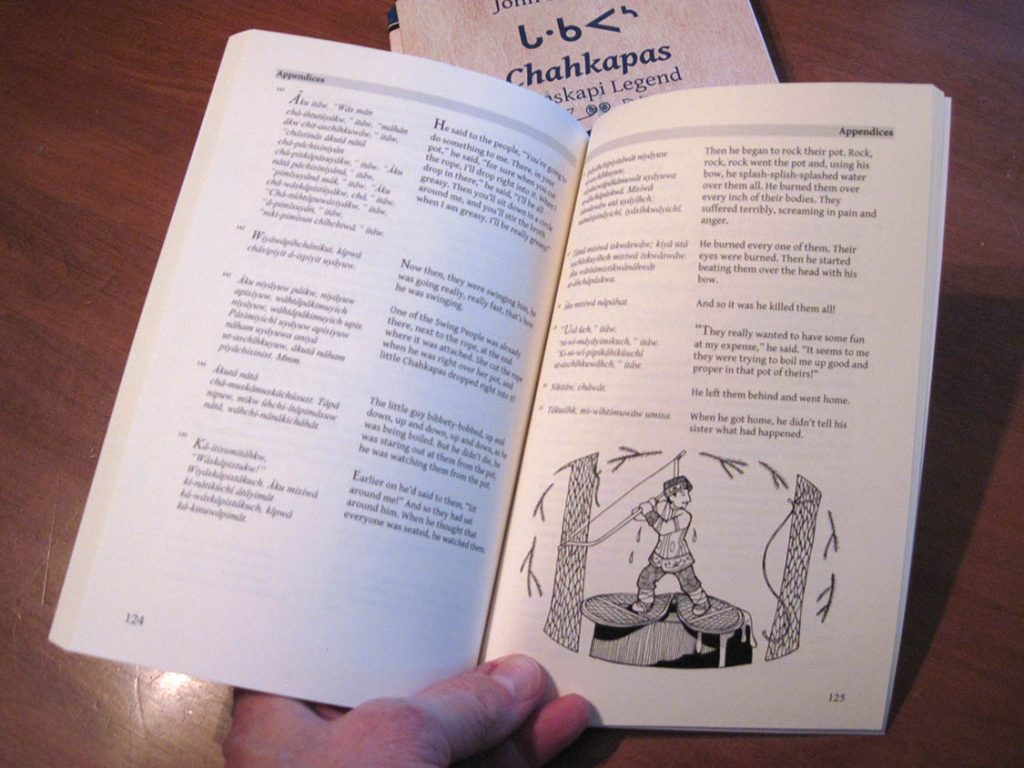

The fourth section of the books provides a display of the Naskapi text rendered in a phonemic spelling (pronunciation) set parallel to the English translation, line-by-line. This is provided so that students of indigenous languages have access to the stories for further study and analysis. Each line of the text is numbered in order to assist readers in finding their place in the stories presented in the other sections of the book.

Parallel Naskapi and English section for linguistic study from the Chahkapas book

Online Resources

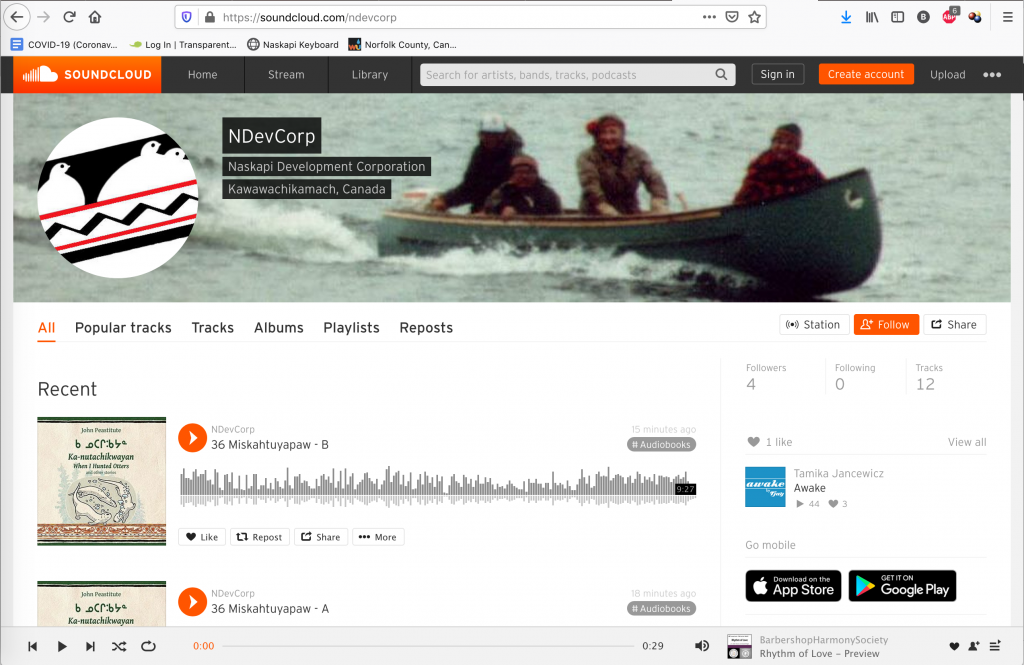

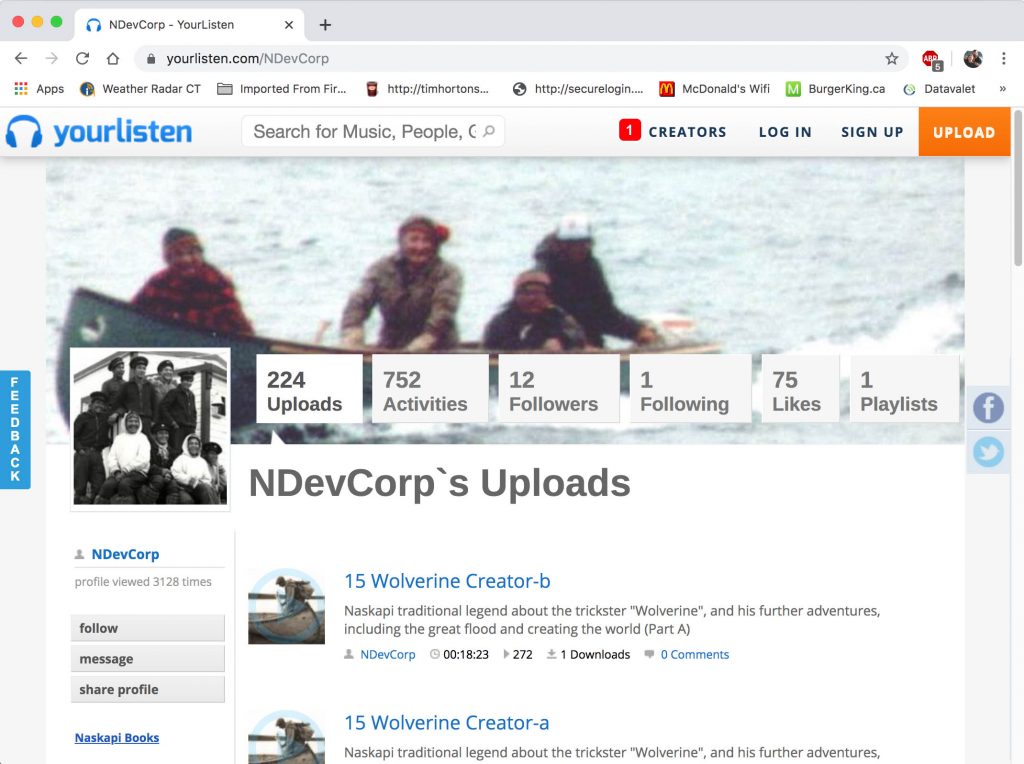

We are also working on producing the audio recordings of the stories so that they are available for airplay on the local Naskapi radio station. These radio programs are also available to listen to online via live-stream or download at the following website: https://soundcloud.com/ndevcorp.

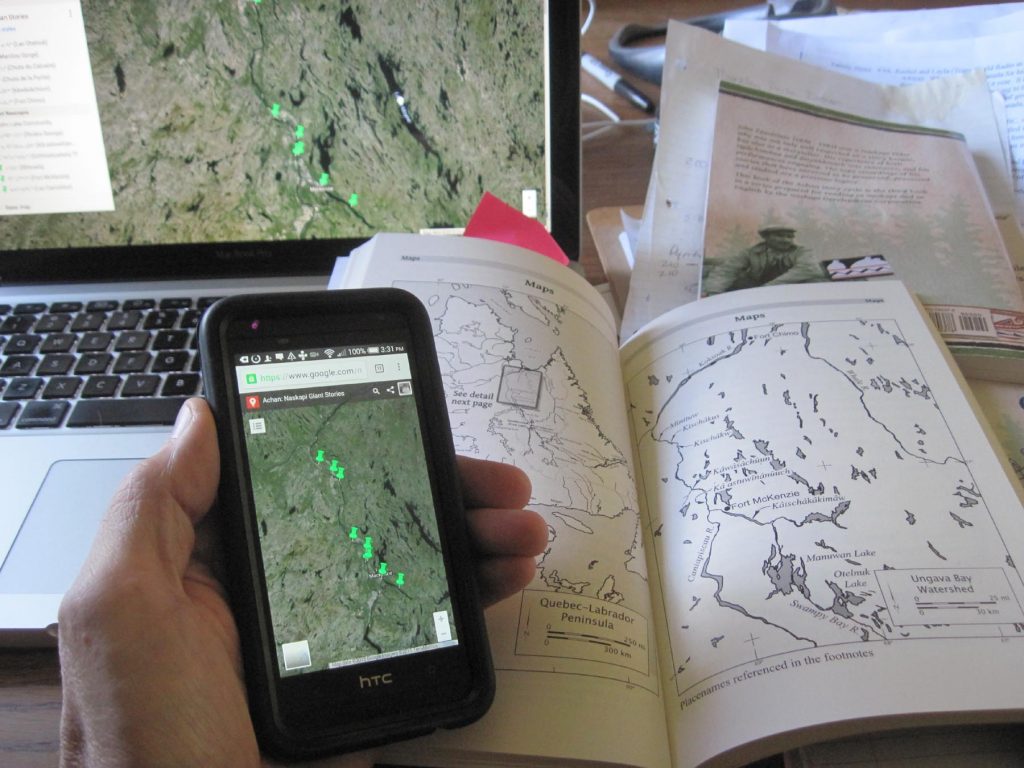

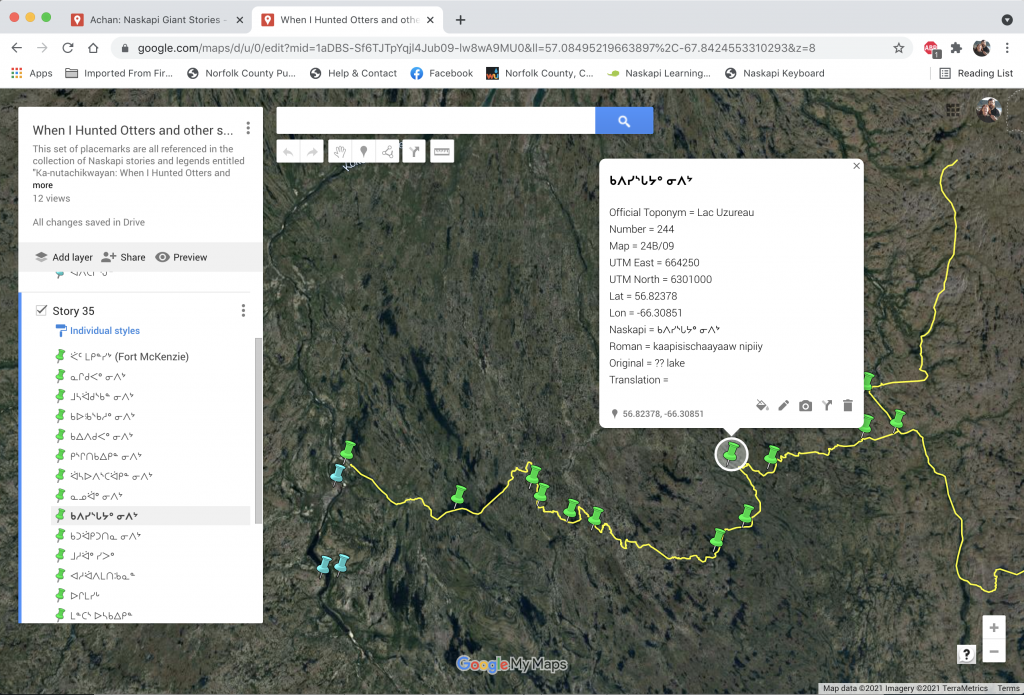

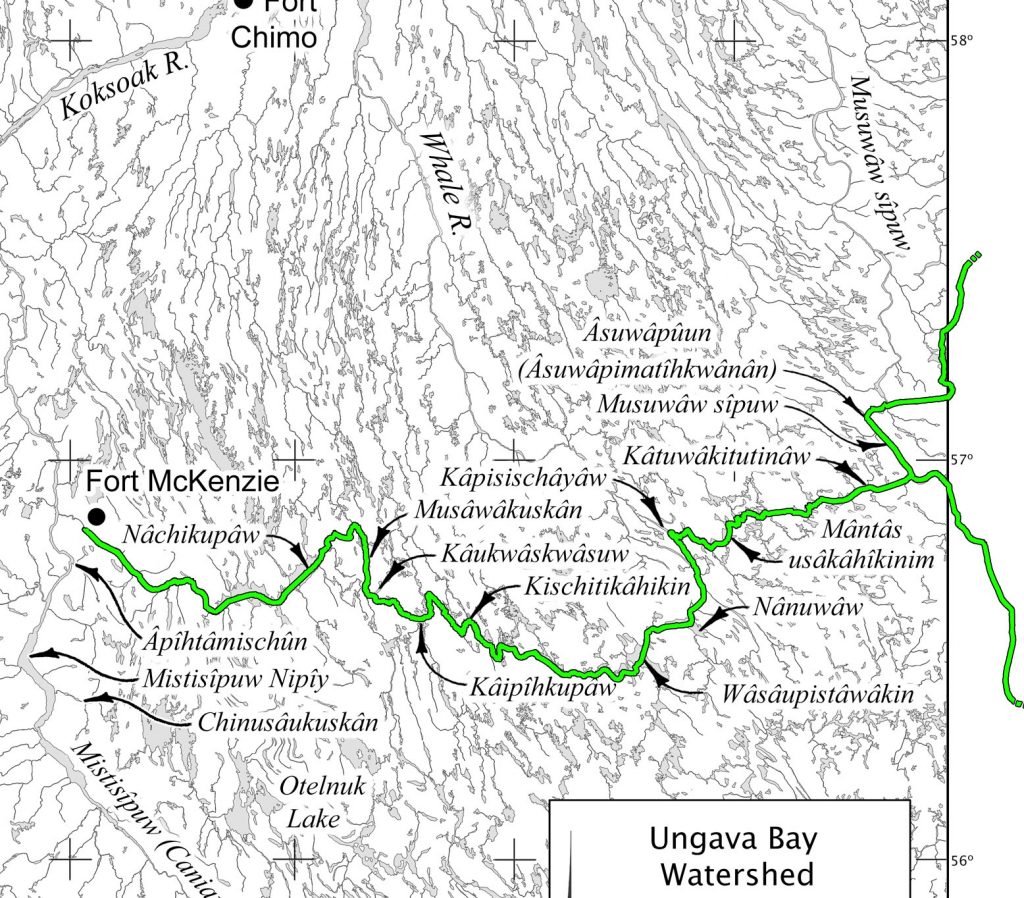

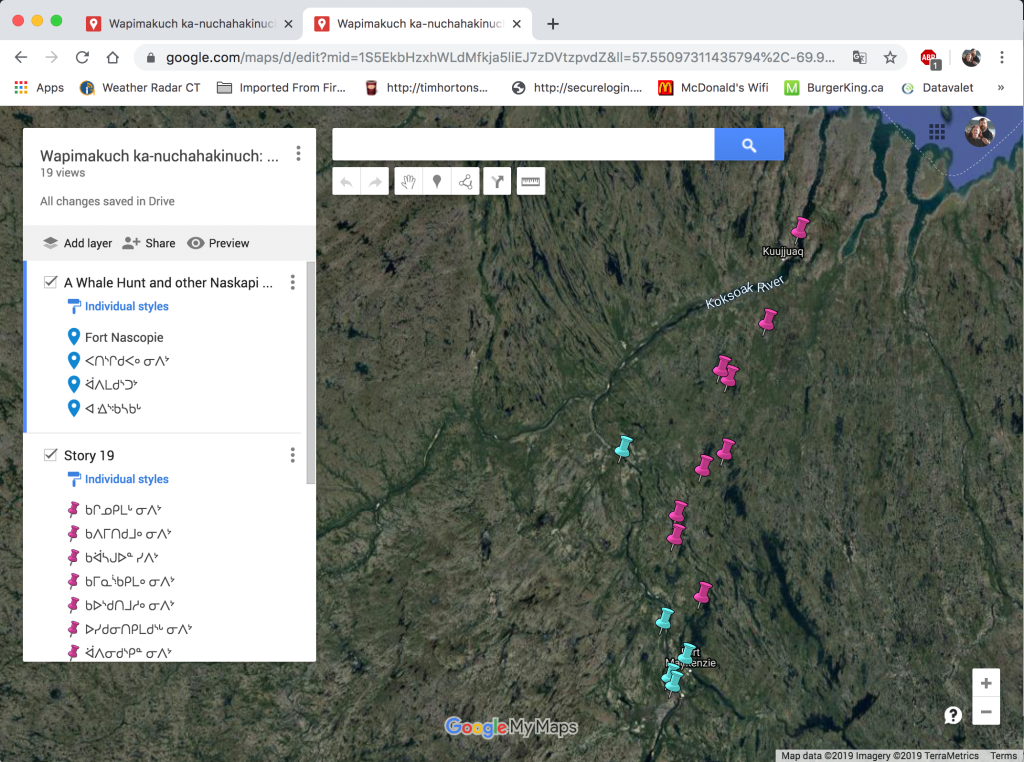

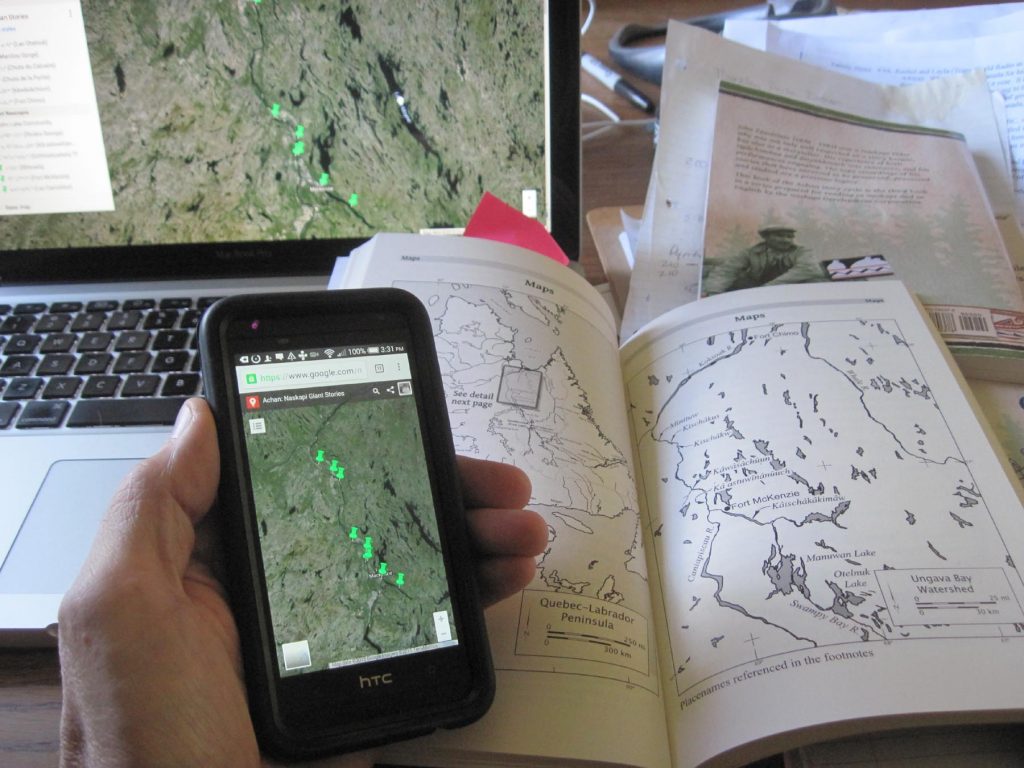

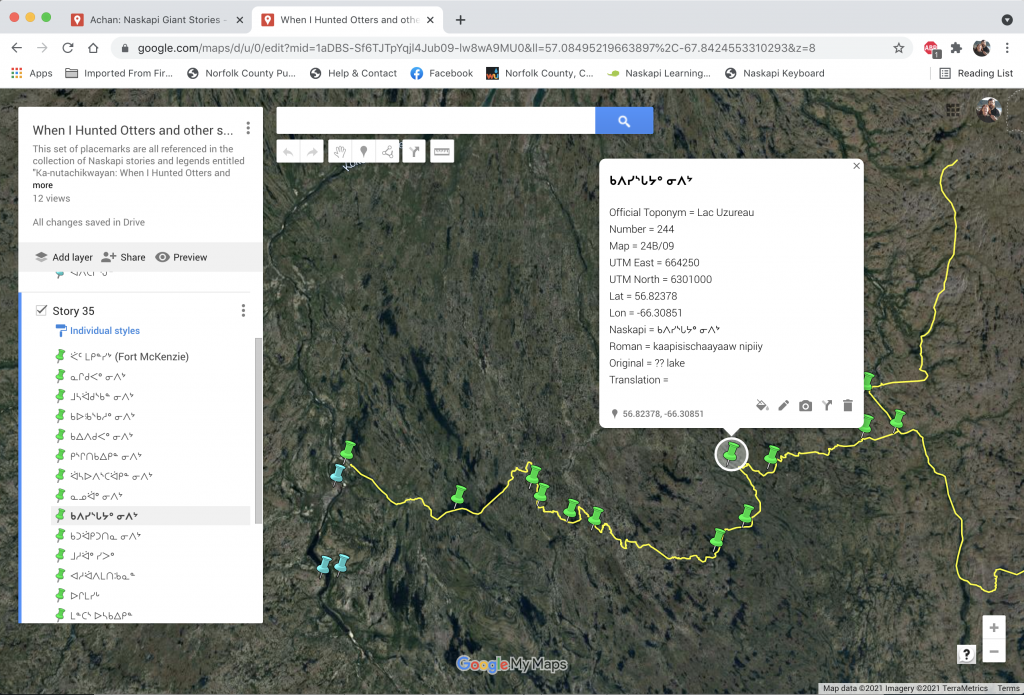

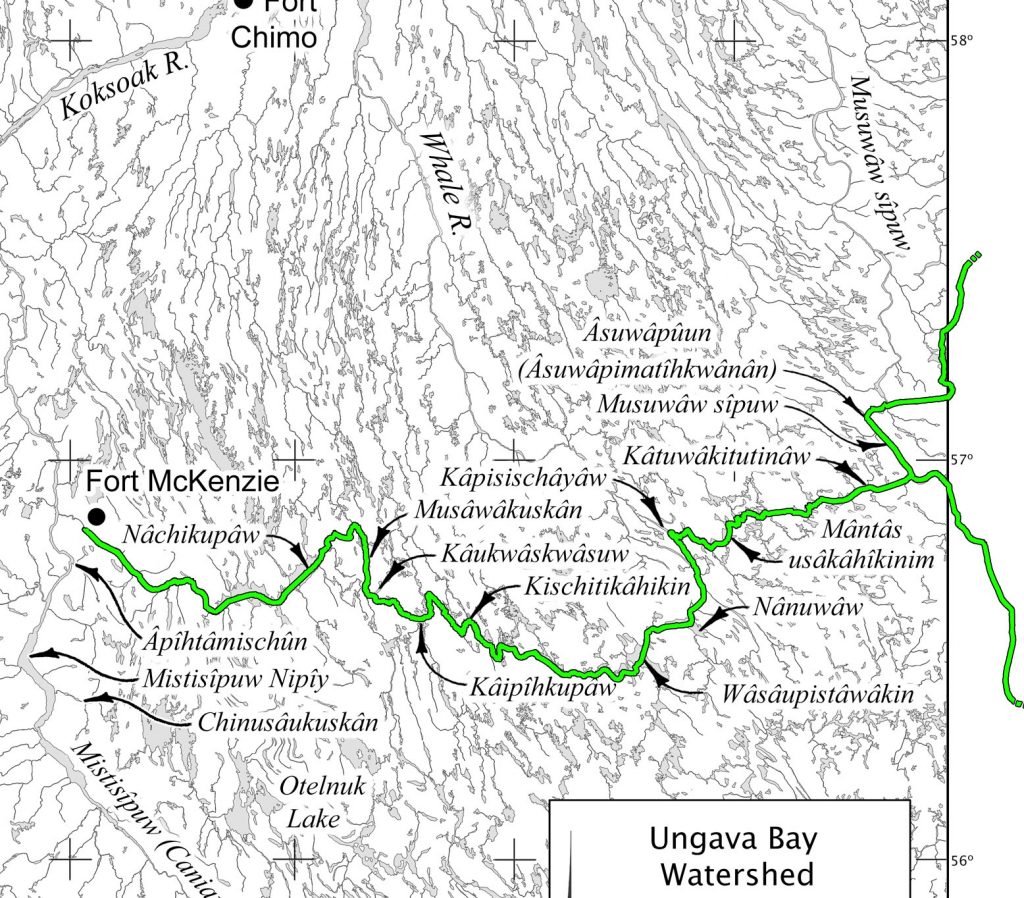

Most of the books that contain tipâchimûna (historical accounts) also feature printed maps, labeled in Naskapi and in English with the traditional Naskapi placenames in their territory. Like most indigenous cultures, the Naskapi people have a close affinity with the land, the physical resources and the animals that live there with them. Many of the stories have detailed accounts of travel and survival on the land, and references to real places where these events actually happened.

Printed and online GIS map from the Achan: Naskapi Giant Stories book

The books with maps also contain geographic information system (GIS) data with online content so that users can explore these sites using online services such as Google Maps or Google Earth. Here is an example link to the maps from our 2021 book,

Ka-nutachikwayan: When I Hunted Otters and other stories.

https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1aDBS-Sf6TJTpYqjl4Jub09-lw8wA9MU0&usp=sharing

Google Maps showing John Peastitute’s route for his “Journey East” story in the Otter Hunting book.

https://googleearthcommunity.proboards.com/thread/8007/when-hunted-otters-stories-nutachikwayan

Detail of map printed on page 65 in the Otter Hunting book

Naskapi History by Naskapi People

Even though what usually comes to mind when this project is discussed are the legends of talking animals and amazing events, which are mainly covered in the genre of âtiyûhkinch featured in the first few volumes of this series. But in recent years the series has transitioned to books containing exclusively stories told in the tipâchimûna genre, that of true and eyewitness accounts. The present volume, When I Hunted Otters and the two previous volumes A Whale Hunt (2019) and Caught in a Blizzard (2017) contain stories of caribou hunting, otter hunting, fox hunting and even whale hunting; stories about journeys across their broad and beautiful land in all of the extremes winter and summer weather; and accounts of danger and disaster, starvation and exposure, drownings, murder and war. Through it all we can hear of the resilience of the Naskapi people, their dependence upon and knowledge about the resources of the land, and their relationships with each other and the early visitors to their territory, both European (mainly fur traders) and strangers from other indigenous groups. Some readers may find the stories raw or disturbing, but they reflect the hard realities of survival (and often, death) in a landscape that while vast and breathtaking can be unforgiving.

In these stories we gain a perspective of life on the land through the eyes of the people who lived it. While they remain stories that were originally meant to be heard in an oral context, told in certain seasons of the year, at night in family groups by the fire, they still provide a real history of the Naskapi people that can help us and indeed their own younger generations to understand who they are and are where they are from.

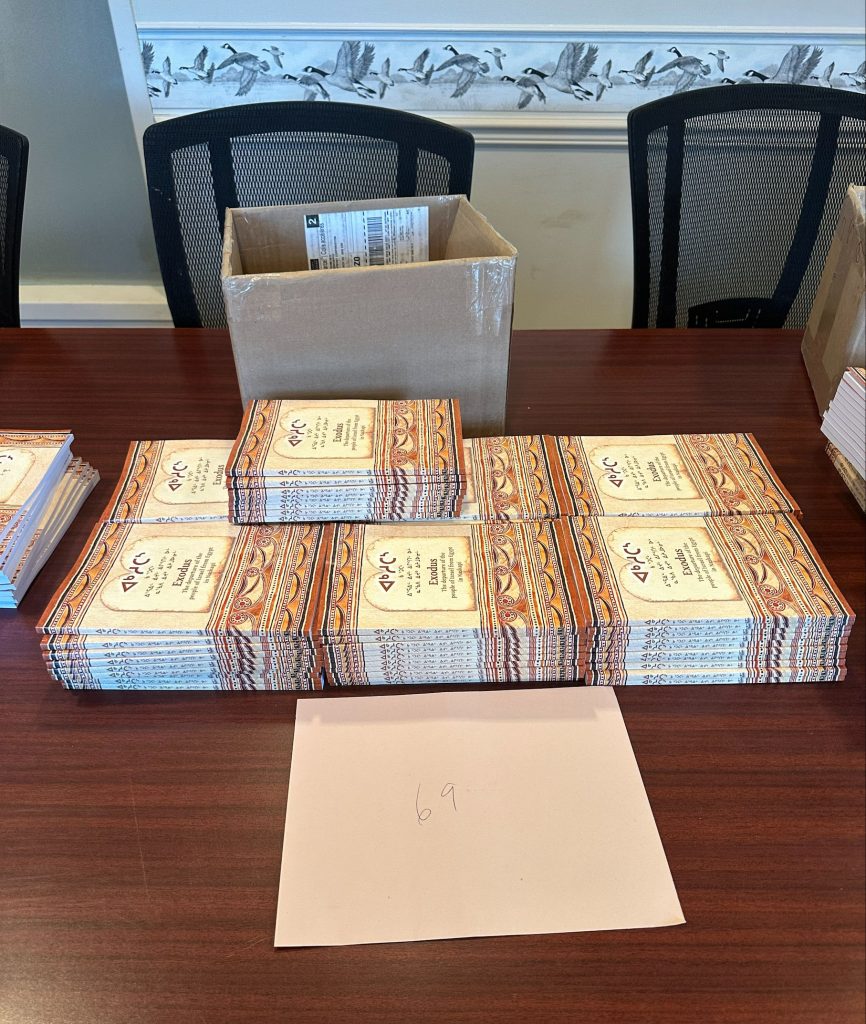

How to get the books

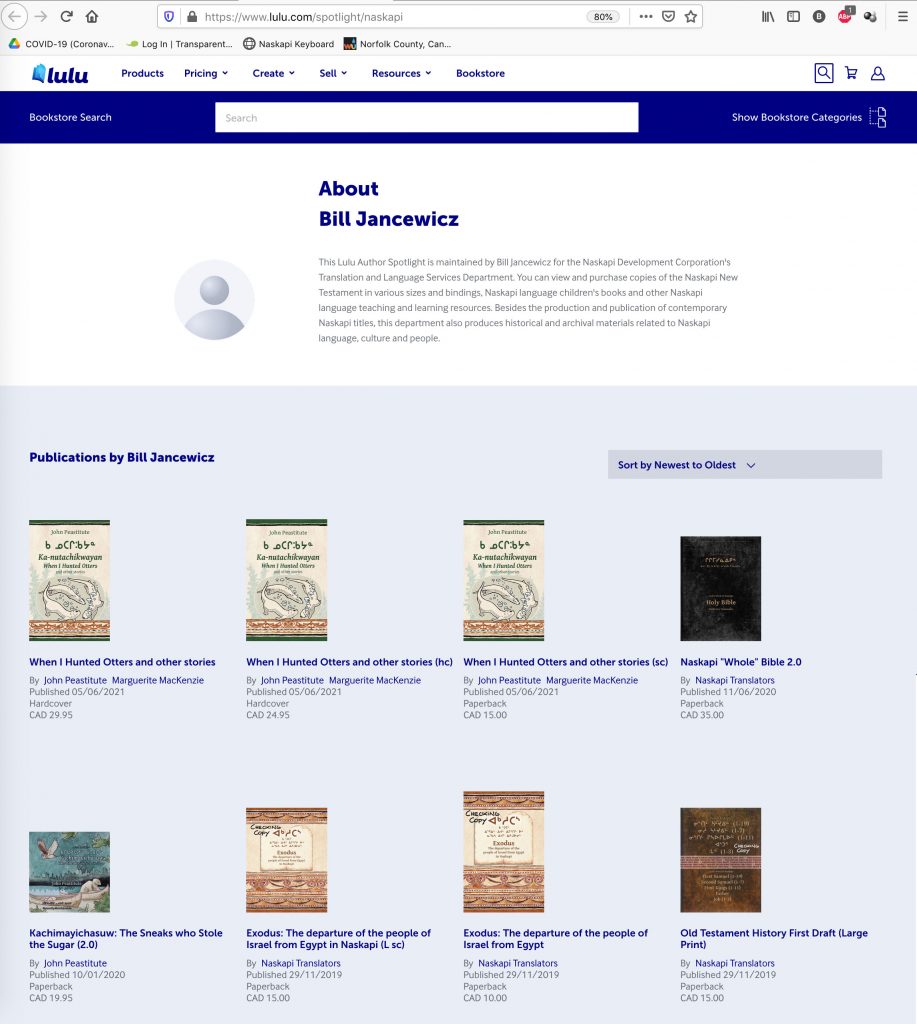

The best place to purchase books in this collection is at the Naskapi Development Corporation Head Office, in Kawawachikamach, Quebec. There a modest inventory of all the books are kept on hand so that anyone in the Naskapi community can come and buy these books at a very reasonable cost. Costs are kept lower than retail by purchasing the books wholesale in bulk quantities. But not everyone is able to purchase the books in person there.

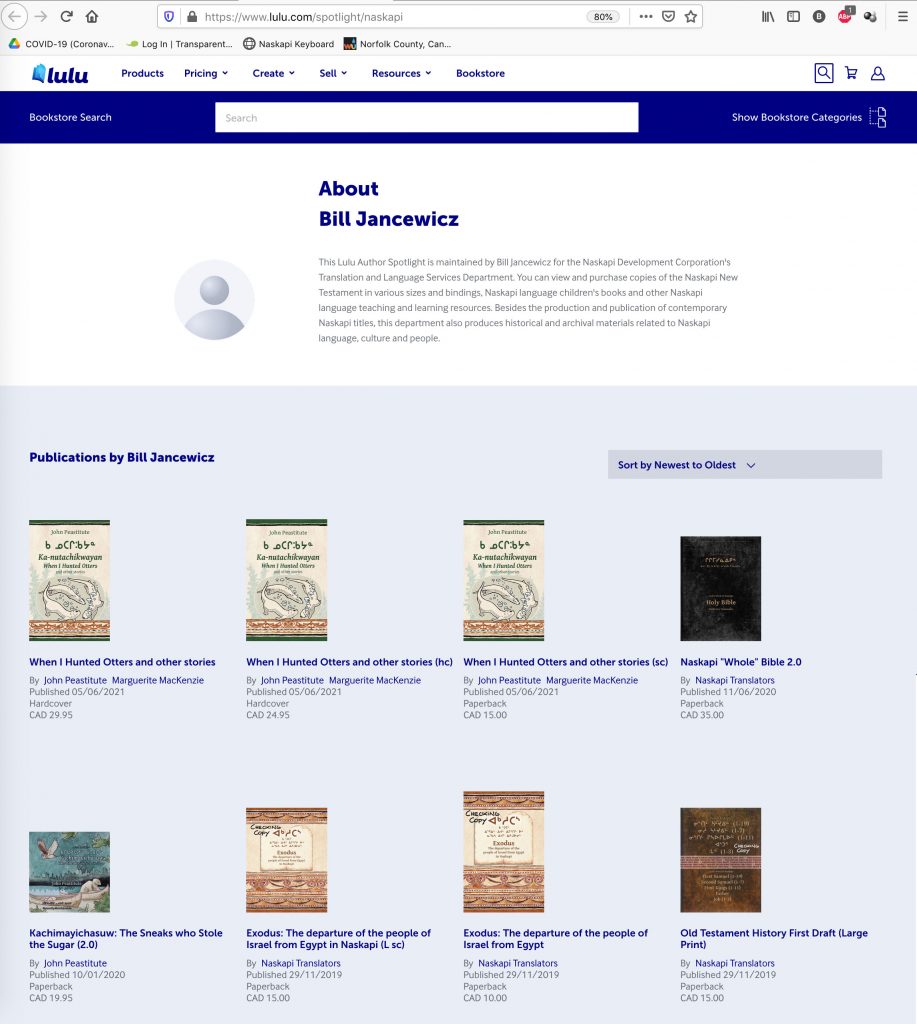

We help the Naskapi Development Corporation maintain an online bookstore where these and all the other Naskapi books can be purchased. You can visit the Naskapi Development Corporation “Storefront”, hosted by Lulu.com, at this link:

http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/naskapi

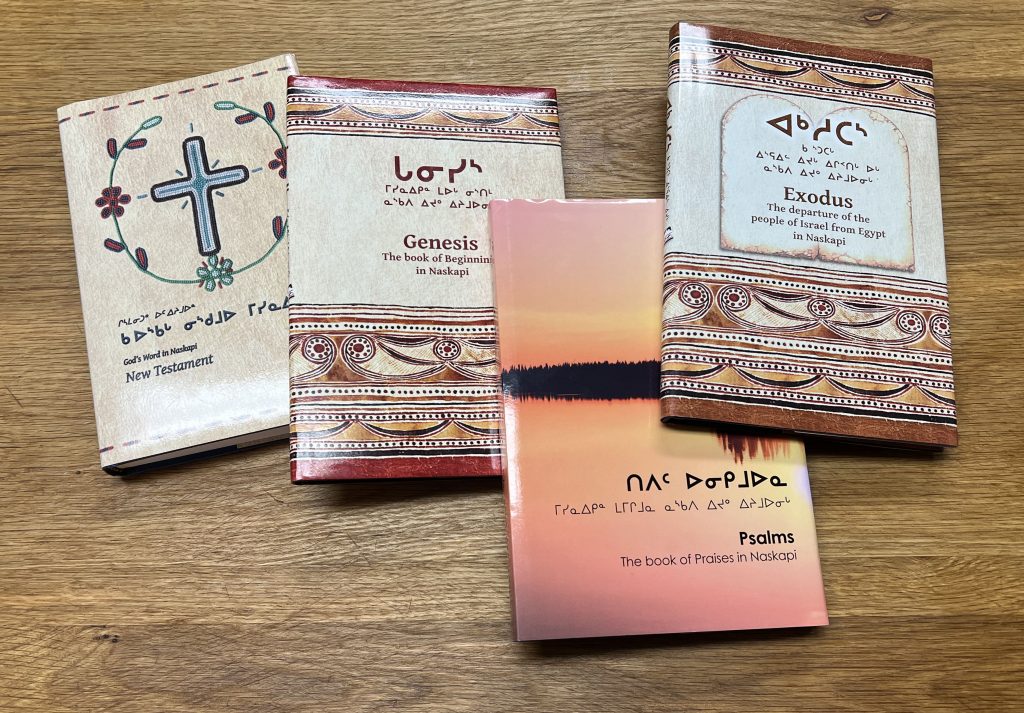

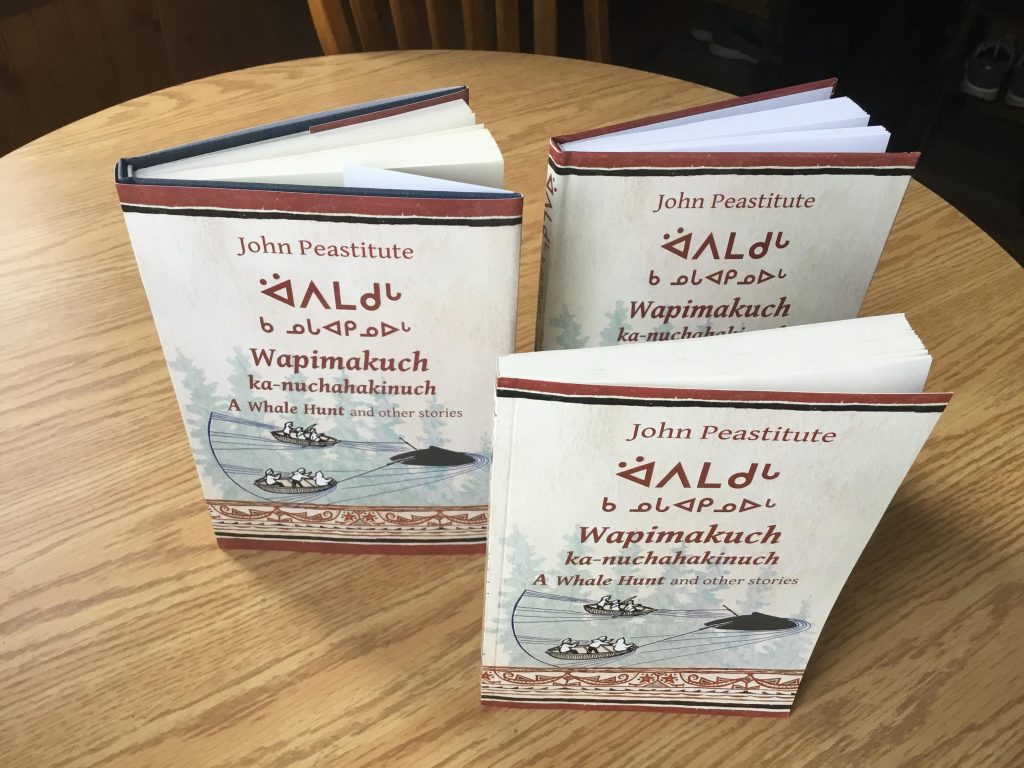

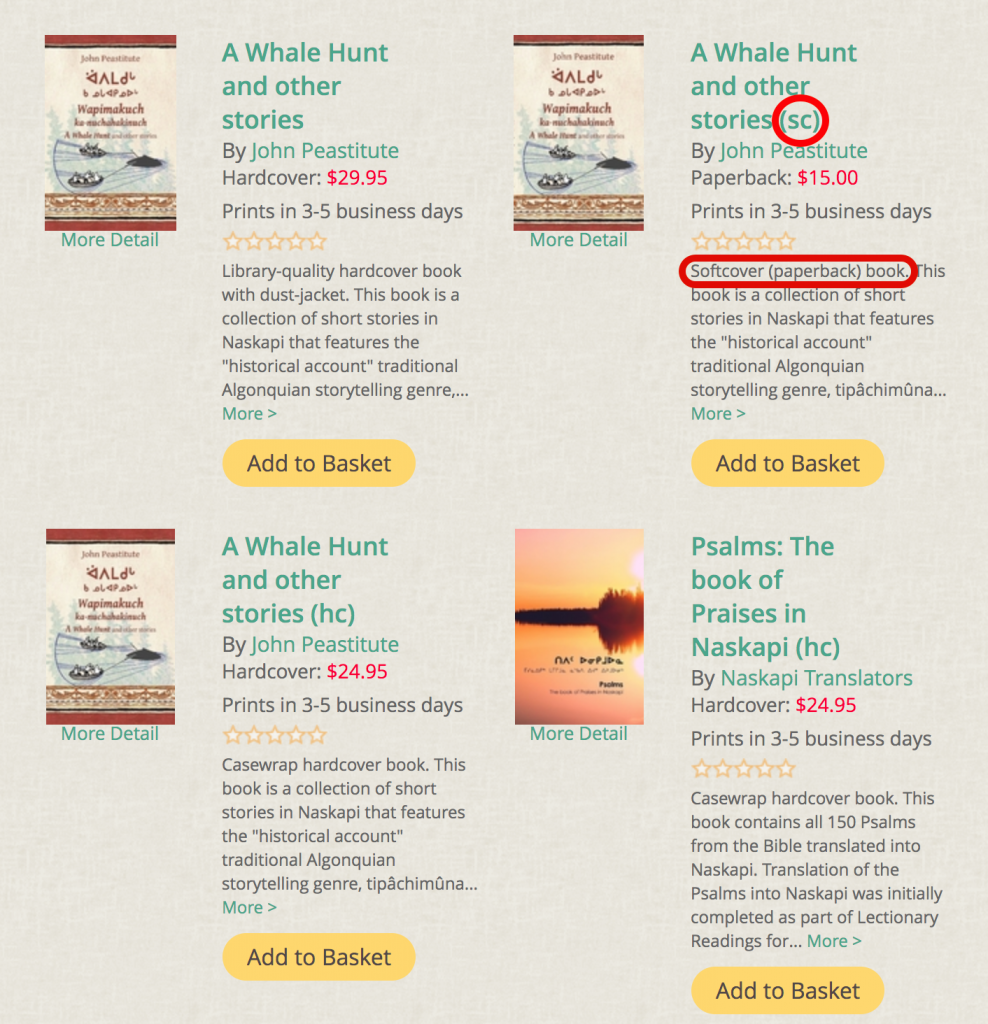

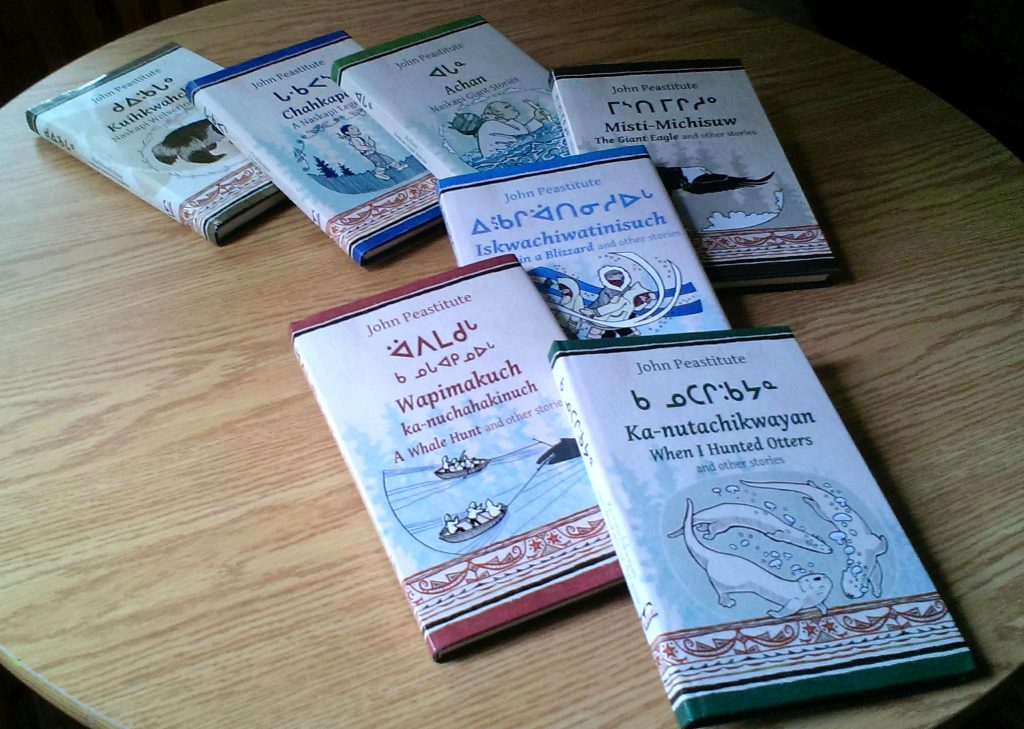

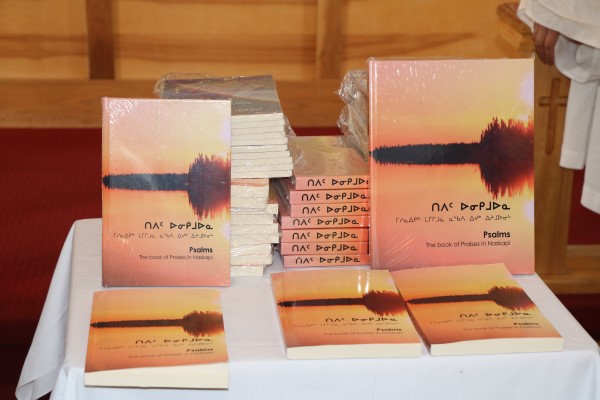

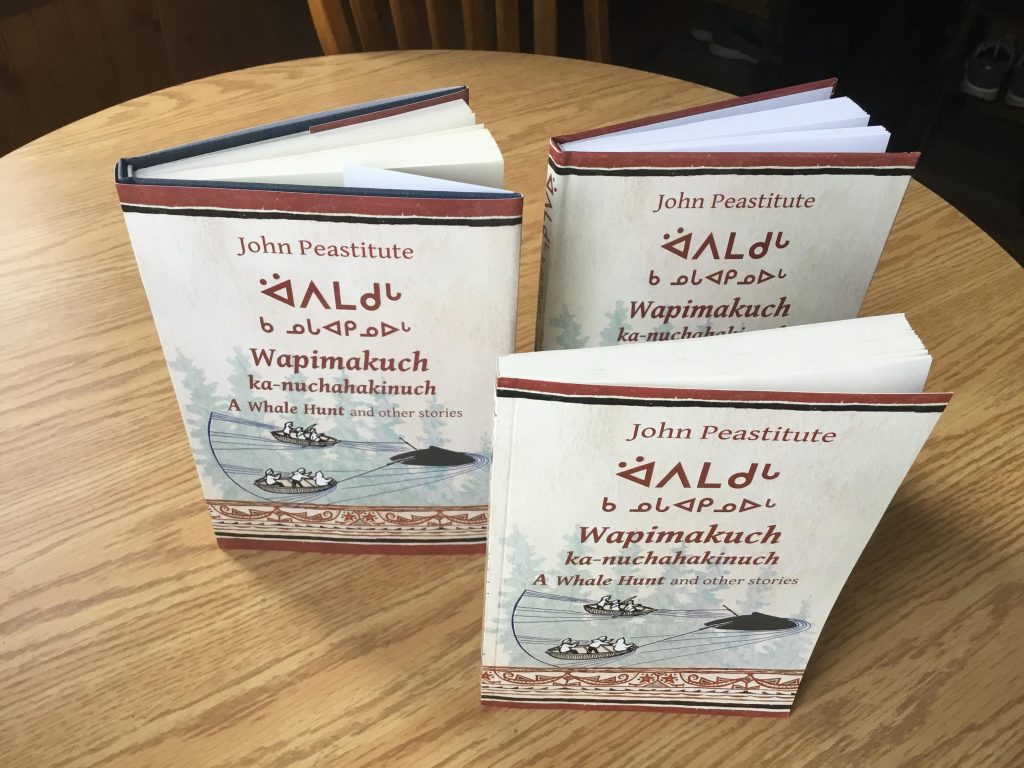

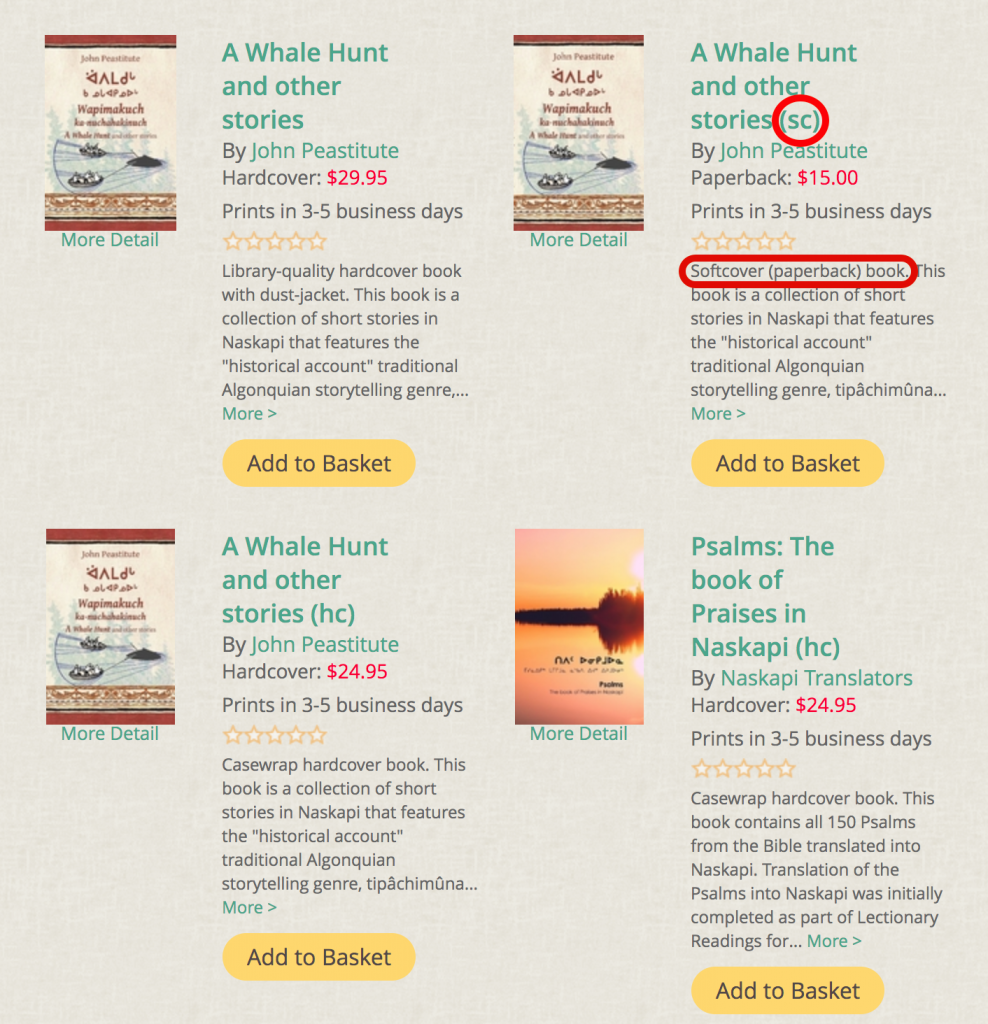

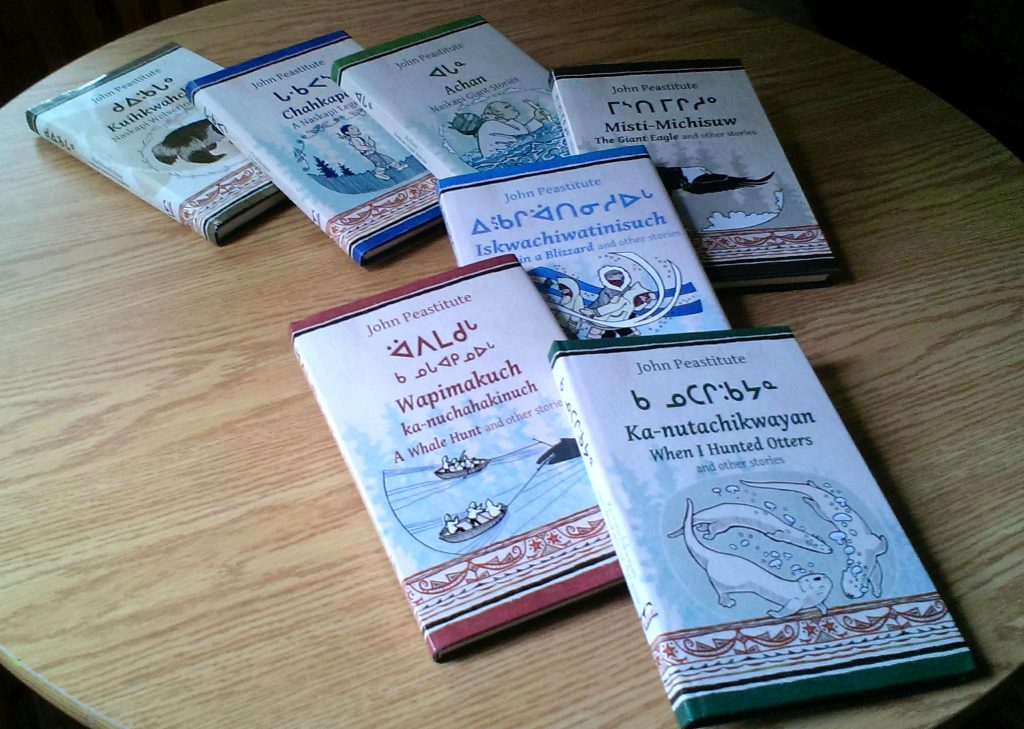

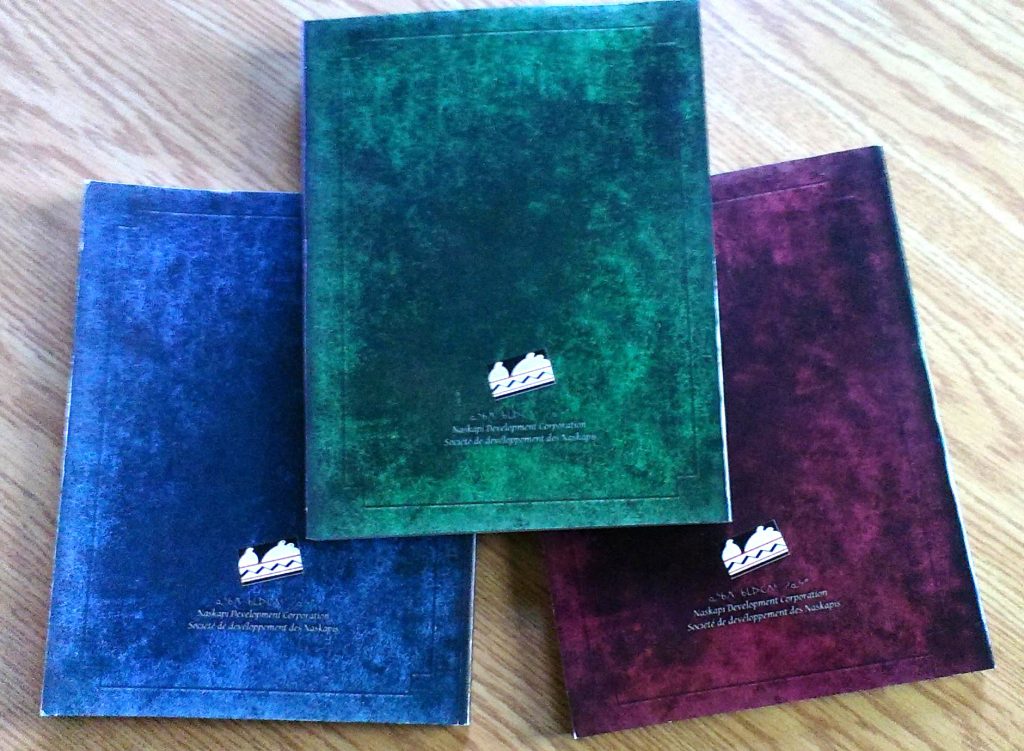

There you can find not only the books in the Naskapi Legend and Stories Project, but all the Naskapi language resources that the NDC makes available to the Naskapi community. The books in this series all come in three editions: economical paperbacks (sc), durable hardcover (hc), and deluxe, library-quality clothbound books with dust jackets.

There you can find not only the books in the Naskapi Legend and Stories Project, but all the Naskapi language resources that the NDC makes available to the Naskapi community. The books in this series all come in three editions: economical paperbacks (sc), durable hardcover (hc), and deluxe, library-quality clothbound books with dust jackets.

Cloth-bound, library-quality with dust jacket; hard cover (hc); economical paperback (sc)

Cloth-bound, library-quality with dust jacket; hard cover (hc); economical paperback (sc)

You will find, in the online store, that each edition is listed separately. If you are interested in a particular edition such as the economical paperback (sc), be sure to select a book that has “(sc)” in the title, like this:

Three editions of the Whale Hunt volume

As we pointed out earlier, Ka-nutachikwayan: When I Hunted Otters and other stories, is our seventh and final volume in this stage of the Naskapi Legends and Stories project. You can find all the titles that have been published in this series available at our online store.

It is our privilege be a part of helping to make these traditional Naskapi stories available to Naskapi people today and for future generations. We are grateful for the opportunity.

It is our privilege be a part of helping to make these traditional Naskapi stories available to Naskapi people today and for future generations. We are grateful for the opportunity.

–Bill Jancewicz, project facilitator,

for the entire Naskapi language team, the linguistic consultants, and the illustrator.

References and recommended further reading:

Armitage, Peter. 1992. “Religious Ideology among the Innu.” In Religiologiques: Sciences humaines et religion 6 (automne 1992) edited by Guy Ménard. Montreal: UQAM http://www.religiologiques.uqam.ca/

Baldwin, Gordon C. 1970. Talking Drums to Written Word. New York: Norton.

Brittain, Julie, and Marguerite MacKenzie. 2014. “Umâyichîs.” In Sky Loom: Native American Myth, Story, Song, 379-398. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

———. 2005. “Two Wolverine Stories.” In Algonquian Spirit: Contemporary Translations of the Native Literatures of North America, 121–58. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

———. 2011. “Translating Algonquian Oral Texts.” In Born in the Blood: On Native American Translation, 242–74. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Canada, Government of. 1975. James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA). Ottawa, ON: Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development.

http://www.naskapi.ca/documents/documents/JBNQA.pdf.

———. 1984. Northeastern Quebec Agreement (NEQA). Ottawa, ON: Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. http://caid.ca/AgrNorEasQueA1974.pdf.

Carlson, Hans M. 2009. Home is the Hunter: The James Bay Cree and their Land. Vancouver BC: UBC Press.

Ellis, C. Douglas. 1989. “Now Then, Still Another Story—”: Literature of the Western James Bay Cree: Content and Structure. Winnipeg, MB: Voices of Rupert’s Land.

Hammond, Marc. 2010. Monts-Pyramides and the Naskapis: A report to Nunavik Parks Department of Renewable Resources, Environmental and Land Use Planning Department. Kuujjuaq, Quebec: Kativik Regional Government.

Henriksen, Georg. 2010. Hunters in the Barrens: The Naskapi on the Edge of the White Man’s World. New York: Berghahn Books.

———. 2009. I Dreamed the Animals: Kaniuekutat: The Life of an Innu Hunter. New York: Berghahn Books.

Lefebvre, Madeleine, Robert Lanari, José Mailhot. 1999 & 2004. Sheshatshiu-atanukana mak tipatshimuna. St. John’s, NL: Labrador Innu Text Project. https://www.innu-aimun.ca/english/stories/labrador-myths-and-legends/.

MacKenzie, Marguerite. 1980. “Towards a Dialectology of Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi.” PhD thesis, Toronto, ON: University of Toronto. https://www.innu-aimun.ca/english/resources/academic-papers/.

MacKenzie, Marguerite, and Bill Jancewicz. 1994. Naskapi Lexicon / Lexique Naskapi. First Edition. 3 vols. Kawawachikamach, QC: Naskapi Development Corporation. https://dictionary.naskapi.atlas-ling.ca/#!/help

Peastitute, John. 2013. Kuihkwahchaw: Naskapi Wolverine Legends. Edited by Marguerite MacKenzie. Translated by Julie Brittain. Kawawachikamach, QC: Naskapi Development Corporation.

———. 2014. Chahkapas: A Naskapi Legend. Edited by Marguerite MacKenzie. Translated by Julie Brittain. Kawawachikamach, QC: Naskapi Development Corporation.

———. 2015. Achan: Naskapi Giant Stories. Edited by Marguerite MacKenzie. Translated by Julie Brittain. Kawawachikamach, QC: Naskapi Development Corporation.

———. 2016. Misti-Michisuw: The Giant Eagle and other stories. Edited by Marguerite MacKenzie. Translated by Julie Brittain. Kawawachikamach, QC: Naskapi Development Corporation.

———. 2017. Iskwachiwatinisuch: Caught in a Blizzard and other stories. Edited by Marguerite MacKenzie. Translated by Julie Brittain. Kawawachikamach, QC: Naskapi Development Corporation.

———. 2019. Wapimakuch ka-nuchahakinuch: A Whale Hunt and other stories. Edited by Marguerite MacKenzie. Translated by Julie Brittain. Kawawachikamach, QC: Naskapi Development Corporation.

———. 2021. Ka-nutachikwayan: When I Hunted Otters and other stories. Edited by Marguerite MacKenzie. Translated by Julie Brittain. Kawawachikamach, QC: Naskapi Development Corporation.

Preston, Richard. 2002. Cree Narrative: Expressing the Personal Meanings of Events. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Quebec, National Assembly of. 1979. “An Act Respecting the Naskapi Development Corporation.” Québec, QC: Publications du Québec. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cs/S-10.1.

Savard, Rémi. 1971. Carcajou et le sens du monde: récits Montagnais-Naskapi. Troisième édition revue et corrigée edition. Civilisation du Québec 3. Éditeur Officiel du Québec, Québec. http://classiques.uqac.ca/contemporains/savard_remi/carcajou/

carcajou.html.

———. 1985. La Voix des Autres. Positions anthropologiques. Montréal: L’Hexagone. http://classiques.uqac.ca/contemporains/savard_remi/

voix_des_autres/voix_des_autres.html.

Speck, Frank. 1977. Naskapi: The Savage Hunters of the Labrador Peninsula. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Tanner, Adrian. 2014. Bringing Home Animals: Mistissini Hunters of Northern Quebec. St. John’s, NL: ISER Books.

Waldram, James Burgess. 2004. Revenge of the Windigo: The Construction of the Mind and Mental Health of North American Aboriginal Peoples. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

<end>

<end>

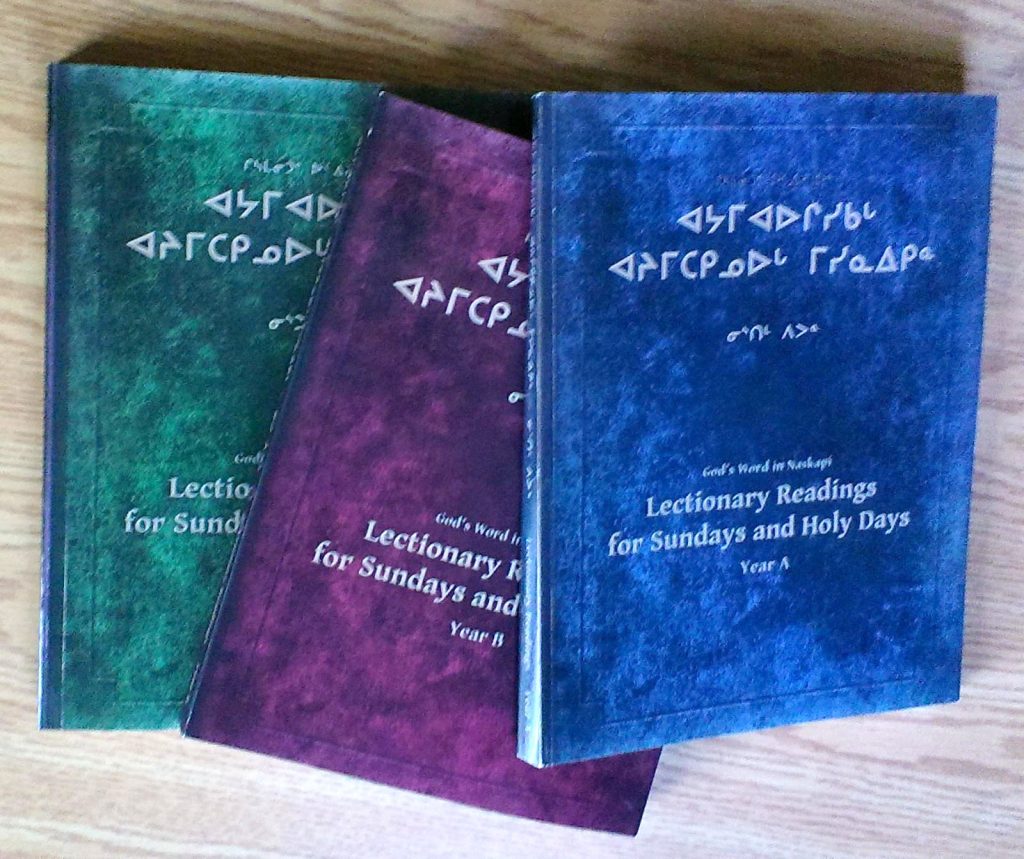

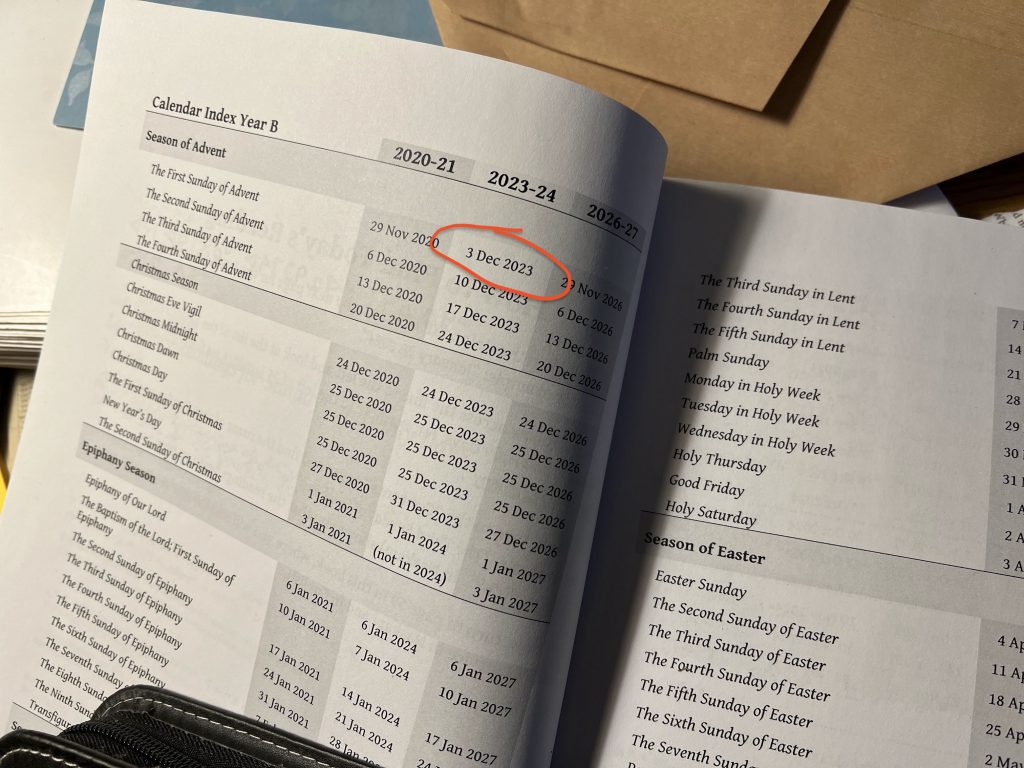

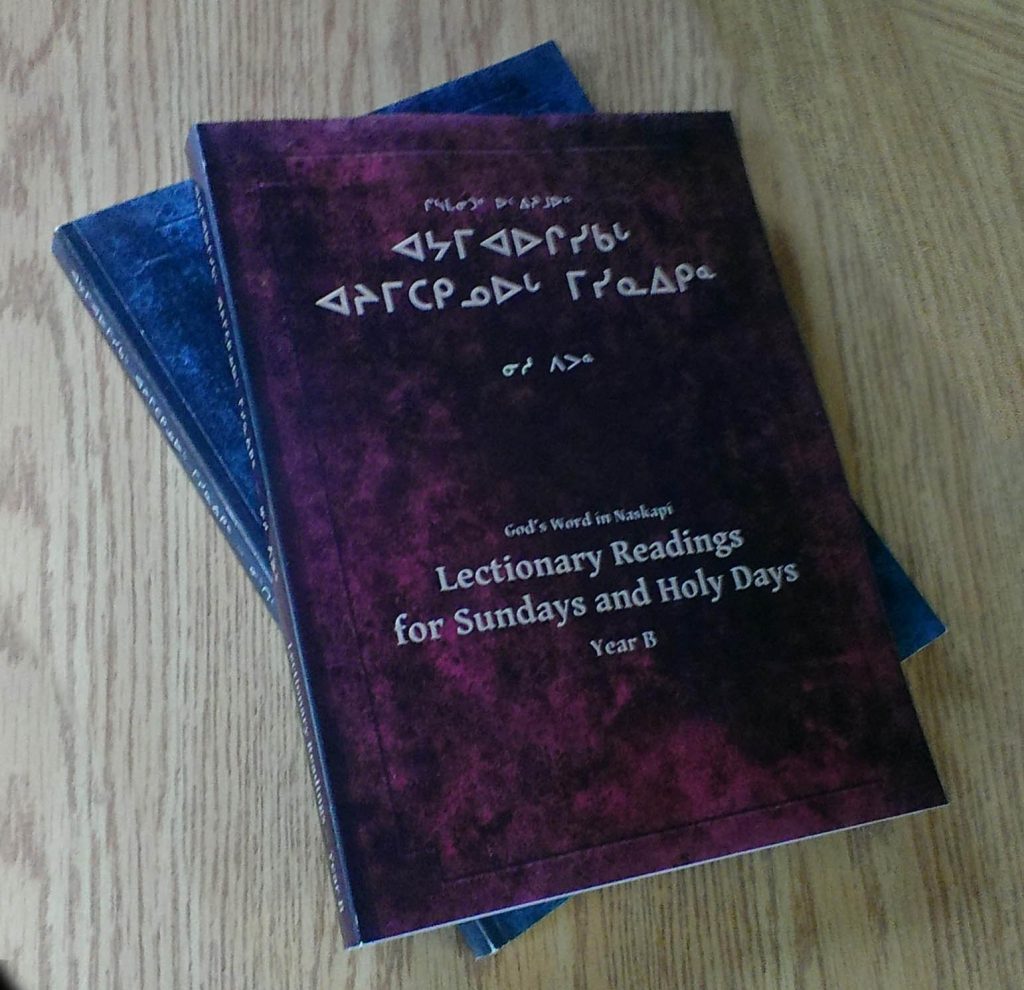

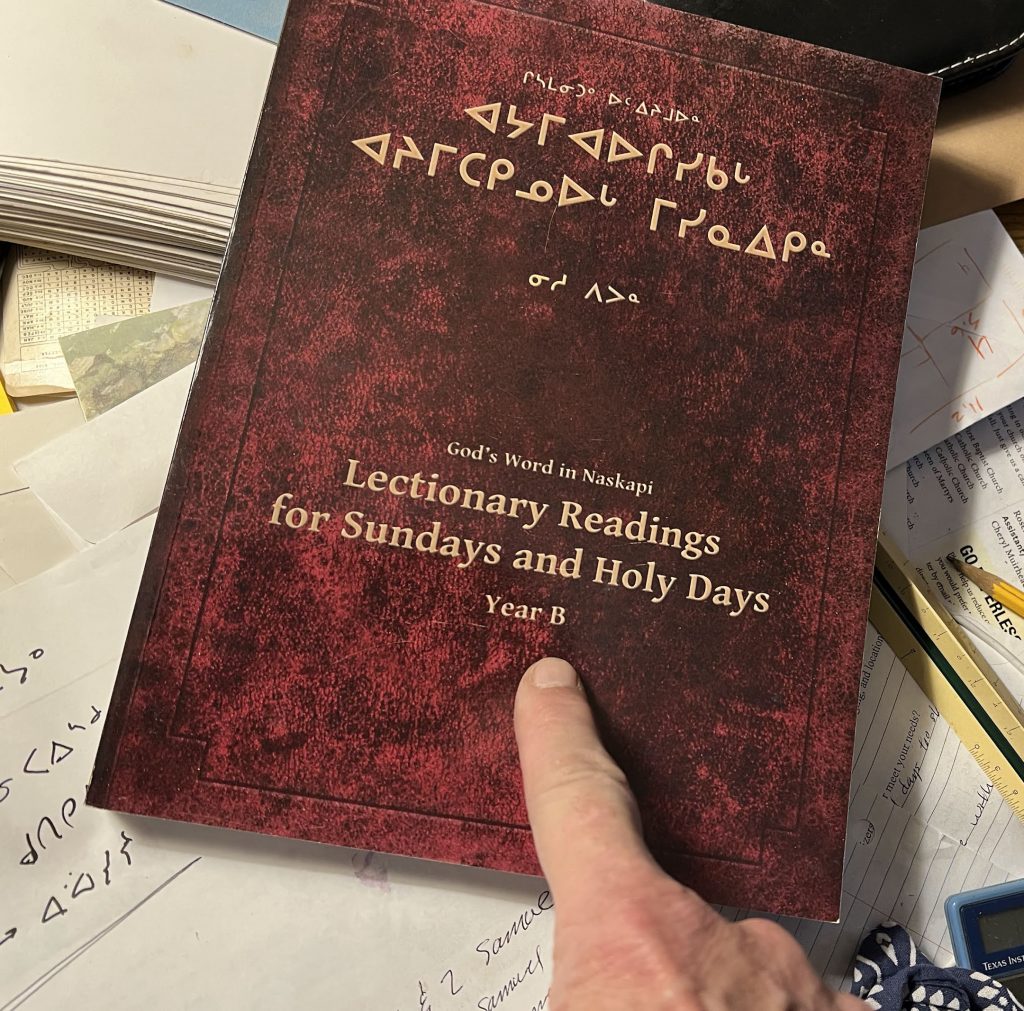

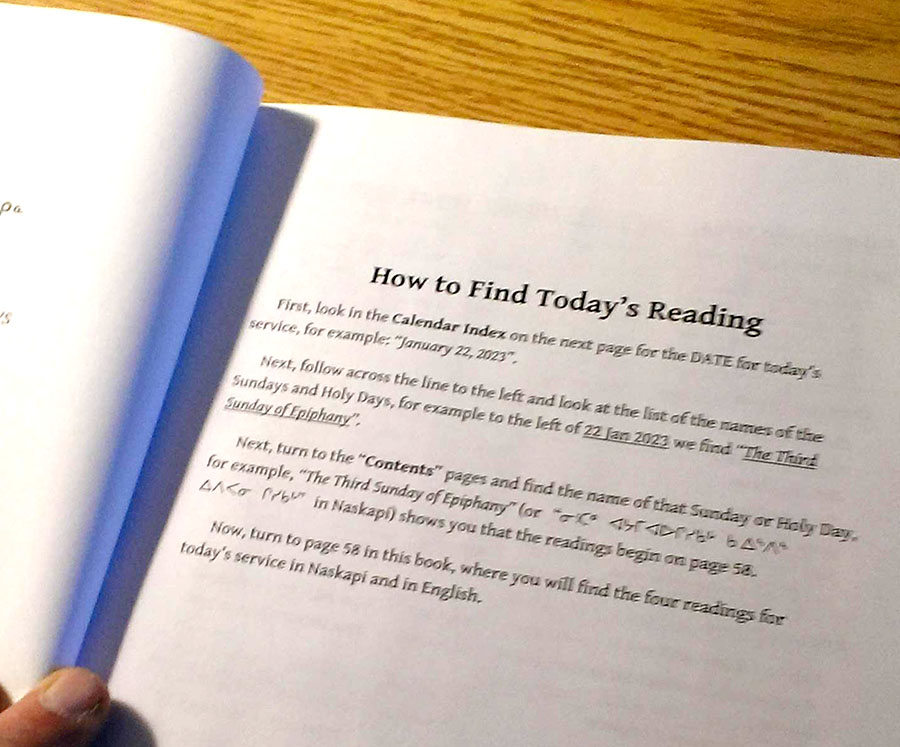

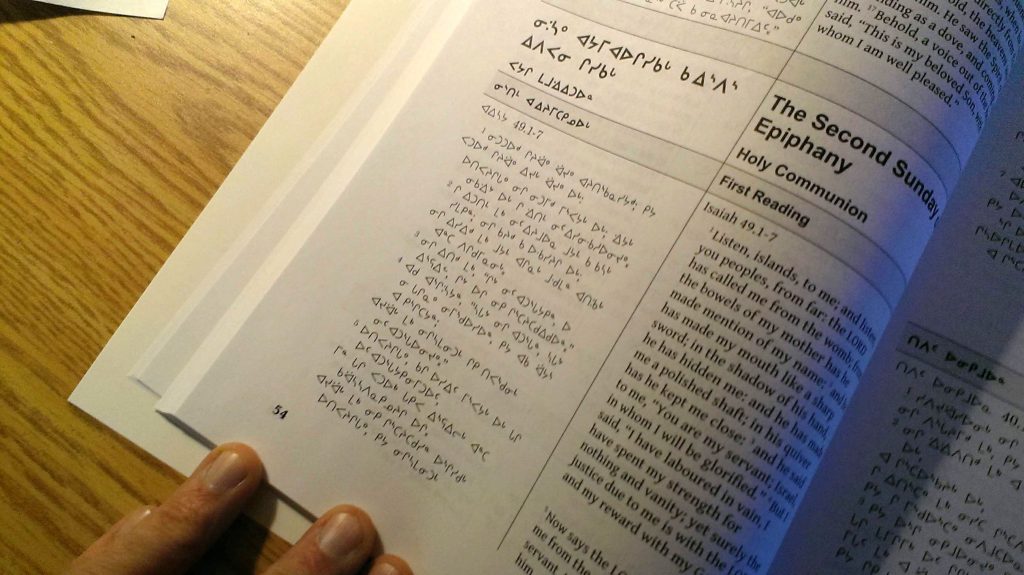

Lectionary “Year B” starts Sunday December 3!

Lectionary “Year B” starts Sunday December 3!

These new Lectionary revisions also feature an updated cover design:

These new Lectionary revisions also feature an updated cover design: December 2023–use the Red Book, “Year B”

December 2023–use the Red Book, “Year B”